Discover Lady Tan’s World

Use the tabs to navigate through the Lady Tan’s World.

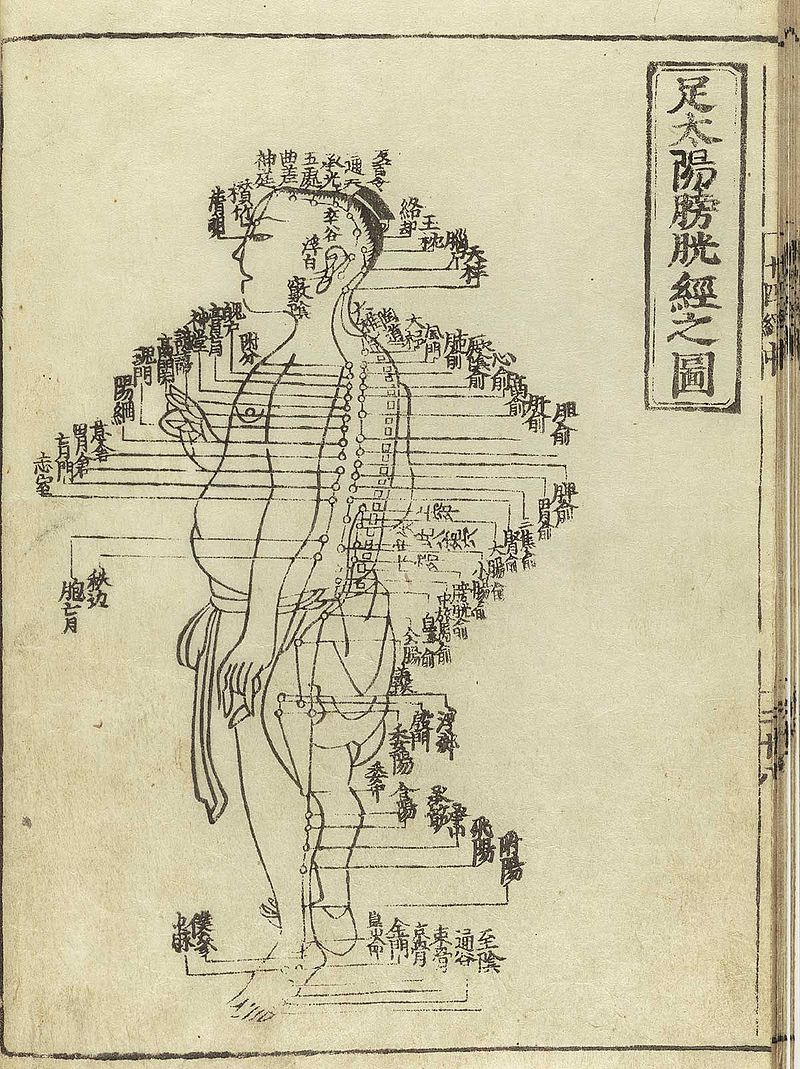

Part 1: Lady Tan and Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Tan Yunxian

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

- The Four Examinations

- The Five Depot Organs

- The Five Elements

- Pulse-taking

- Traditional Chinese Medicinal Herbs

- Angelica

- Atractylodis

- Forsythia

- Ginseng

- Honey Locust Fruit

- Licorice Root

- Lovage

- Mugwort

- Poria Mushroom

- Radish Seeds

- Rehmannia

- White Peony Root

- Moxibustion

- Small Pox and Variolation

Part 2: Historical Ming China

- Ming Dynasty

- History of the Ming Dynasty

- Traditional Hanfu

- Makeup and Hair

- Imperial Scholars

- Imperial Exams

- Civil Badges

- Military Badges

Part 3: Traditions and Culture

- Marriage Bed

- Confucius

- Forensics and Punishments

- The Washing Away of Wrongs

- Cangue

- Punishments and Tortures

- Foot Binding

- Concubines and Eunuchs

- Concubines

- Eunuchs

- Weddings

- Wedding Costume and Headdress

- Three Letters

- Six Etiquettes

- Child Bearing

- Midwives

- Childbirth

- Funerals

- Dragon Boat Festival

- Tea

Part 4: People and Places

- Garden of Fragrant Delights

- Humble Administrator’s Garden

- Qiao’s Family Compound

- Places

- Grand Canal

- Sampan

- Wuxi

- Lake Tai

- Forbidden City

- People

- Emperor Hongzhi

- Empress Zhang

Marriage Bed

A marriage bed refers to a type of bed that was traditionally used in China during the Ming Dynasty, which lasted from 1368 to 1644. The marriage bed held significant cultural and symbolic importance as it represented the union between a husband and wife and served as an essential piece of furniture in a newlywed couple’s home.

Ming Dynasty marriage beds were typically large, intricately carved wooden beds with elaborate designs and decorative motifs. They were crafted using high-quality materials and adorned with intricate carvings, lacquerwork, and paintings, showcasing the skilled craftsmanship of the time. The bed frames were often made from durable hardwood, such as rosewood or elm, and featured ornate details, such as dragons, phoenixes, flowers, and auspicious symbols.

References

Article: Red, Pagoda. Chinese Beds: Rooms Within Rooms. Medium. 4 Apr 2010

Article: Li, Carrie. “The Age of Elegance: Ming Dynasty Furniture.” Sotheby’s. 25 Sep 2020

Confucius

Confucius, an influential figure in ancient China, revolutionized education by advocating for its widespread accessibility. As the first teacher in China, he dedicated himself to imparting knowledge and establishing teaching as a noble profession. His teachings and philosophies, compiled in a book known as the Analects, became the cornerstone of Confucianism—a way of life that emphasized ethical behavior, moral values, and social harmony.

During the Ming Dynasty, which spanned from 1368 to 1644, the government embraced the principles of Neo-Confucianism. This philosophy, an evolution of Confucian thought, served as the guiding ideology for the Ming administration. Neo-Confucianism emphasized the understanding of one’s place in society’s hierarchical structure, the promotion of harmonious relationships within communities, and the reverence for family ties. These principles profoundly influenced the governance and social fabric of Ming society, shaping its moral and ethical standards.

Confucius’s teachings, preserved in the Analects, emphasized the importance of cultivating virtues, such as benevolence, righteousness, and filial piety. His emphasis on education and the pursuit of moral excellence left a lasting impact on Chinese culture and society, including the Ming Dynasty, where Confucian principles played a central role in shaping individuals’ conduct, social interactions, and the governance of the empire.

References

Article: Rattini, Kristin Baird. “Who Was Confucius?” National Geographic. 26 March 2019

Article: Chin, Annping. Confucius: Chinese Philosopher. Britannica. 20 July 1998

Forensics and Punishment

The Washing Away of Wrongs

T’zu’s The Washing Away of Wrongs (Hsi yüan chi lu) is an ancient book on forensic medicine, considered the oldest surviving text of its kind in the world. It was published in 1247 and served as a guide for magistrates conducting investigations. The book provides valuable insights into early Chinese understanding of pathology and morbid anatomy. While there are different versions of the book, the earliest existing version was published during the Yuan Dynasty and consists of fifty-three chapters divided into five volumes.

The first volume of the book discusses an imperial decree issued by the Song Dynasty regarding the examination of bodies and injuries. The second volume focuses on notes and methods for conducting post-mortem examinations. The remaining volumes, three to five, provide detailed descriptions of the appearances of corpses resulting from various causes of death, along with methods for treating specific injuries. This groundbreaking work can be regarded as the world’s first written book on forensic science, predating the second book on the subject by about 450 years, which was written in Italy during the 17th century.

T’zu’s The Washing Away of Wrongs stands as a significant contribution to the field of forensic medicine, offering invaluable knowledge and techniques for investigating and understanding the human body in a medicolegal context. Its historical importance lies in its role as an early pioneer in the field, laying the foundation for the development of forensic science in the centuries to come.

Cangue

The cangue (/kæŋ/), also known as tcha, is a wooden device used as a form of public humiliation, corporal punishment, and occasional torture in East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia until the early 20th century. This punishment involved wearing a wooden board around the neck and wrists as a means of disciplining delinquents. The cangue was specifically designed to be worn in public, intensifying its humiliating effect. During the Ming Dynasty, the use of the cangue was occasionally combined with other extreme measures, such as foot amputation or long-term public exhibition (known as youli). Typically, individuals sentenced to wear the cangue endured its punishment for a period ranging from one month to half a year, although rare cases involved lifelong confinement.

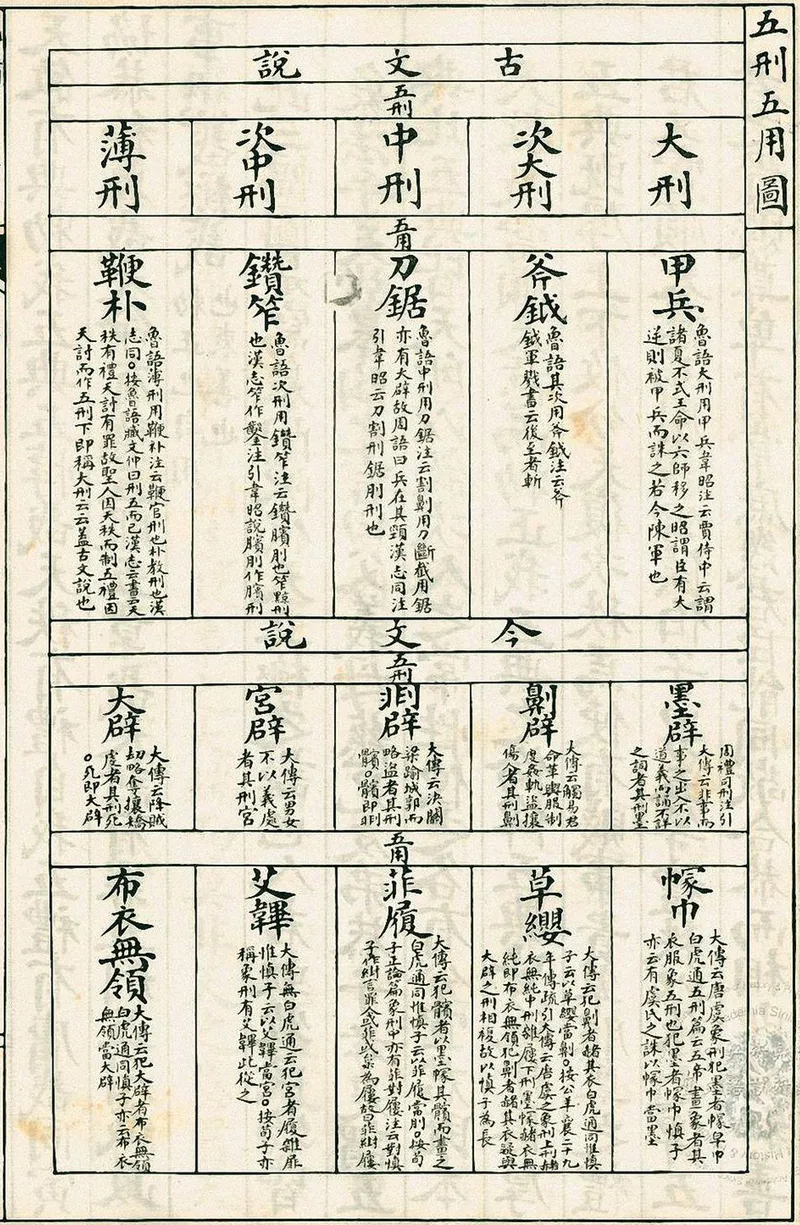

Other Forms of Torture and Punishment

During this period, five main forms of punishment emerged, which included tattooing, amputation of the nose or feet, removal of reproductive organs, and death. One particularly brutal method was Lingchi (凌遲), also known as the slow process, lingering death, or slow slicing. This form of torture and execution was practiced in China from around 900 CE until its abolition in the early 1900s. Lingchi involved inflicting a multitude of cuts on the victim’s body, earning it the grim nickname “death by a thousand cuts.”

Another common form of punishment during this time was beatings, which often served as a prevalent means of discipline. Offenders would be subjected to lashings with bamboo rods or canes, and the severity of the punishment would vary depending on the seriousness of the crime. Unfortunately, in some cases, the beatings would prove fatal, leading to the untimely death of the punished individual.

References

Article: Minh, Le Thanh. Washing Away of Wrongs-The First Forensic Science Book Ever Written in the World. WorldKings: World Records Union.

Article: Chin, Annping. Confucius: Chinese Philosopher. Britannica. 20 July 1998.

Wikipedia: Cangue. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cangue)

Image Gallery: Images of Cangue. Granger Historical Picture Archive.

Wikipedia: The Five Punishments. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Punishments)

Website: Chinese Torture 酷刑 Kù xíng. Chinasage.

Article: Jiahui, Sun. “Death by Flaming Shoes and Hundred Cuts: Disturbing Methods in Ancient Chinese Torture.” The World of Chinese. 8 April 2023.

Article: Seaver, Carl. “The History of Punishment and Torture in Ancient China.” History Defined. 22 July 2022.

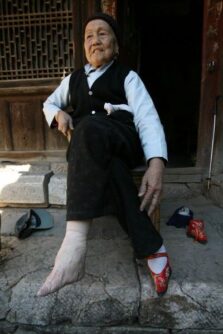

Foot Binding

Foot binding was a practice that emerged during the Ming Dynasty in China and reached its peak during the Qing Dynasty. It involved the tight binding of young girls’ feet to alter their shape and size. The process typically started at a young age, around 5 to 6 years old, when the feet were still developing. The goal was to achieve the ideal of the “golden lotus” foot, a symbol of beauty and status in Chinese society.

The foot binding process was excruciatingly painful and physically debilitating. The feet were tightly wrapped with long strips of cloth, gradually forcing the toes to bend downward and under the sole. This resulted in the arch of the foot becoming highly arched and the foot itself becoming much smaller. The bindings were often tightened over time, causing immense discomfort and restricting the movement of the foot.

Foot binding was practiced primarily among the elite and upper-class families, as it was considered a status symbol and a way to demonstrate a woman’s refinement and adherence to cultural norms. It was believed that small, delicate feet enhanced a woman’s femininity and made her more desirable for marriage.

Despite the widespread practice of foot binding during the Ming Dynasty, it was not officially endorsed by the government. In fact, some Ming officials and intellectuals criticized foot binding, recognizing its harmful effects on women’s health and mobility. However, the practice persisted due to its deep-rooted cultural significance and societal pressure.

Foot binding continued to be practiced until the early 20th century when it was officially banned in 1912 during the Republican era. The banning of foot binding marked a significant milestone in the movement for women’s rights and equality in China, as it aimed to eradicate a practice that caused immense suffering and limited women’s freedom of movement.

References

Website: Main Types of Chinese Lotus Shoes. Textile Research Centre Leiden.

Concubines and Eunuchs

Concubines

The Ming Dynasty, spanning from 1368 to 1644 AD, is hailed as a period of remarkable governance and stability. However, beneath its achievements lay a disturbing reality concerning the treatment of imperial concubines. Ming emperors, notorious for their cruelty, amassed vast numbers of concubines, some exceeding 9,000 in their harems. These women were often forcibly taken from their homes and condemned to a life of captivity, unable to leave except for their assigned roles in the emperor’s bedchamber. Compounded by the practice of foot binding, which immobilized them, the concubines had to be carried naked to the emperor.

The founder of the Ming Dynasty, The Hongwu Emperor, left an indelible mark on history. Rising from humble origins as a penniless monk, he evolved into a powerful warlord and established a reign characterized by both triumphs and brutalities. Behind closed doors, The Hongwu Emperor subjected his concubines to unimaginable torture, driven by his pride and jealousy. To maintain control even beyond his death, he initiated a tradition of killing or burying concubines alongside him. This practice persisted among his successors, such as Yongle and Hongxi, until it was finally abolished by the Zhengtong Emperor in 1464, allowing concubines to fear only the loss of favor rather than their lives.

The Yongle Emperor, famous for constructing Beijing’s Forbidden City, wielded dictatorial power, implementing various reforms in military, economic, and educational spheres. However, his reign was marred by a dark episode of cruelty. Allegations of a concubine’s affair led to the Yongle Emperor orchestrating a mass execution of 2,800 women from his harem, including young girls. While this tragedy is absent from official records, it is recounted in writings by Lady Cui, one of the emperor’s concubines who was absent during the massacre. Shortly after, Lady Cui and 15 remaining concubines were hung in the Forbidden City’s halls on the day of Yongle’s funeral, cementing a legacy of brutality within the palace.

The treatment of concubines during the Ming Dynasty reveals a distressing aspect of an otherwise celebrated era of Chinese history. It serves as a stark reminder of the power dynamics and contradictions that permeated the ruling class. While the Ming Dynasty achieved remarkable feats in governance and exploration, the plight of concubines underlines the darker underbelly of this period, highlighting the profound complexities and inherent cruelties that coexisted alongside the dynasty’s many accomplishments.

Eunuchs

The Ming Dynasty, renowned for its governance and stability, had a dark side characterized by the treatment of imperial concubines. Despite its achievements, Ming emperors displayed cruelty by amassing thousands of concubines, who were forcibly taken from their homes and confined to a life of captivity. Compounded by the practice of foot binding, the concubines were entirely dependent on their assigned roles in the emperor’s bedchamber and had to be carried naked to him. This distressing reality reveals the profound complexities and inherent cruelties that coexisted with the dynasty’s accomplishments.

In addition to the mistreatment of concubines, the Ming Dynasty witnessed the influential role of eunuchs within the imperial court. Eunuchs, castrated men, held positions of power and managed the day-to-day affairs of the court since the Han Dynasty. Although they could not establish dynasties of their own, they possessed considerable political influence due to their proximity to the emperor. Ming emperors, who had thousands of concubines, were not concerned about potential rivals impregnating them, further empowering the eunuchs.

While eunuchs were often portrayed as villains in Chinese dramas, some of them made significant contributions. For instance, eunuch Zhao Gao played a pivotal role in the fall of the Qin Dynasty. Rising through the ranks to become a trusted advisor to Emperor Qin Shi Huang, Zhao Gao orchestrated a coup after the emperor’s death, resulting in the installation of a puppet emperor. However, his actions ultimately led to the downfall of the dynasty. Despite these instances of corruption, some eunuchs, such as Cai Lun and Zheng He, contributed to Chinese culture and history through inventions like paper and exploratory voyages.

The use of eunuchs in China came to an end with the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in the early 20th century. In 1924, the last eunuchs were banished from the Forbidden City, and the practice that had spanned millennia finally came to an end. With the last imperial eunuch’s passing in 1996, this chapter of ancient Chinese history reached its conclusion.

References

Article: Parkes, Veronica. “The Ming Dynasty Concubines: A Life of Abuse, Torture and Murder for Thousands of Women.” Ancient Origins. 2 July 2018.

Article: Mingren, Wu. “The Fascinating Life of a Chinese Eunuch in the Forbidden City” Ancient Origins. 5 August 2020.

Article: Cartwright, Mark. “Eunuchs in Ancient China” World History Encyclopedia. 27 July 2017.

Article: Graham-Harrison, Emma. “China’s last eunuch spills sex secrets” Reuters. 16 March 2019.

Weddings

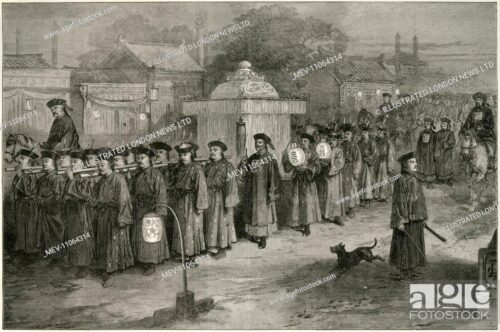

Palanquin Procession

In a Ming Dynasty wedding, the palanquin procession played a central role in showcasing the grandeur and pomp of the occasion. The palanquin, a lavishly decorated carriage carried by bearers, symbolized the noble status and importance of the bride and groom. The procession, accompanied by traditional music and dancers, made its way through the streets, captivating the onlookers with its splendor. The palanquin itself was adorned with intricate silk fabrics, embroidered designs, and auspicious symbols, reflecting the couple’s social status and aspirations. The procession not only added a touch of glamour to the wedding but also served as a public display of the couple’s union, announcing their entrance into married life with grace and extravagance.

Wedding Costume and Headdress

Ming Dynasty wedding costumes and headdresses were significant symbols of cultural identity and social status during this period. The attire worn by the bride and groom reflected the grandeur and elegance associated with wedding ceremonies in Ming Dynasty China.

For the bride, the wedding costume consisted of a traditional robe known as a “qun” or “shan,” typically made from silk or satin. These robes were adorned with intricate embroideries, auspicious motifs, and vibrant colors, symbolizing joy, prosperity, and marital bliss. The style of the robe varied depending on the social status and wealth of the family. Wealthier families could afford more elaborate designs with gold thread and precious gemstone embellishments, while commoners opted for simpler designs. The bride’s attire was often complemented by a decorative belt tied around the waist and layers of delicate silk or brocade undergarments.

One of the most distinctive elements of Ming Dynasty wedding costumes was the elaborate headdress worn by the bride. Known as a “phoenix crown,” it was a symbol of nobility and femininity. The crown featured intricate metalwork and was often adorned with precious gemstones, pearls, and intricate motifs of dragons, phoenixes, and flowers. The number of phoenixes depicted on the crown was an indication of the bride’s social status, with higher-ranking brides wearing crowns with more phoenixes. The phoenix crown was usually accompanied by a sheer veil or headpiece that added an air of mystery and elegance to the bride’s ensemble.

In contrast to the bride’s attire, the groom’s wedding costume was more understated but still reflected the cultural traditions of the Ming Dynasty. The groom typically wore a long silk robe, known as a “pao,” adorned with embroidered designs and subtle motifs. The colors of the groom’s robe were often more muted compared to the bride’s, with shades of blue, black, or brown being commonly chosen. The groom’s headdress was simpler than the bride’s crown, often consisting of a silk cap or hat decorated with auspicious symbols, such as dragons or the character for “double happiness.” This symbolized good fortune and marital bliss for the couple.

Overall, Ming Dynasty wedding costumes and headdresses were elaborate and rich in symbolism. They reflected the social status, cultural traditions, and aspirations of the bride and groom, making the wedding ceremonies a visual spectacle and a celebration of love and union.

Three Letters

In Ming marriage traditions, the Three Letters were integral components of the wedding process. The Three Letters consisted of the Betrothal Letter, the Gift Letter, and the Wedding Letter. The Betrothal Letter was exchanged between the families of the bride and groom, formalizing the marriage agreement and outlining important details such as dowry, wedding date, and other arrangements. The Gift Letter followed, indicating the exchange of gifts between the families as a gesture of goodwill and appreciation. Finally, the Wedding Letter was issued on the wedding day, officially declaring the marriage and providing instructions for the ceremonial proceedings. These Three Letters played a crucial role in Ming marriages, signifying the contractual nature of the union and ensuring that all aspects of the wedding were conducted according to tradition and social norms.

Six Etiquettes

In Ming marriage traditions, the Six Etiquettes were fundamental guidelines that governed the entire process of a wedding. These six rituals or etiquettes included proposal, birthday matching, giving of betrothal gifts, selection of the wedding date, sending the bridal sedan, and the wedding ceremony itself.

The first etiquette involved the proposal, where the groom’s family would send a matchmaker to formally propose to the bride’s family. This proposal was a significant step in initiating the marriage process. The second etiquette, known as birthday matching, aimed to ensure compatibility between the bride and groom based on their astrological signs and birthdates. Once the match was deemed suitable, the third etiquette involved the groom’s family presenting betrothal gifts to the bride’s family, demonstrating their sincerity and commitment to the union.

After the betrothal, the fourth etiquette was the selection of the wedding date. This decision involved consulting astrologers and considering auspicious dates for the ceremony. The fifth etiquette was the sending of the bridal sedan, a decorated carriage that carried the bride to the groom’s house. This procession symbolized the bride’s departure from her family home. Finally, the sixth and final etiquette was the wedding ceremony itself, where the couple exchanged vows and participated in various rituals, including the worship of ancestors and the exchange of tea. These Six Etiquettes formed a structured framework that ensured the orderly and culturally significant progression of a Ming wedding.

References

Article: “How to Prepare a Chinese Hanfu Wedding (Ming-style).” NEWHANFU. 6 March 2021

Article: Li, Zhang (Staff Reporter) “Traditional Han Chinese Marriage Customs” China Today. 2 March 2016

Article: Ming Dynasty Wedding Dress: 明新娘服. Dragon’s Armory. 23 December 2020.

Article: “Three Letters and Six Etiquettes of Chinese Marriage” Keats: Learn Chinese in China.

YouTube: “鄧麗君 Teresa Teng 上花轎 Getting On The Flowery Sedan Chair” Channel: HKships4TeresaTeng2. 23 July 2021.

Child Bearing

Midwives

In Ming Era China, midwives held a respected and honored position in society. These experienced women were highly valued for their knowledge and skills in assisting women during childbirth. Midwives were often older individuals who had acquired expertise through years of practical experience rather than formal education. They provided vital support and care to expectant mothers, offering comfort, guidance, and reassurance throughout the birthing process. Their role encompassed monitoring the progress of labor, managing pain, employing traditional Chinese medicine techniques, and attending to the newborn and postnatal care. The respected midwives of the Ming Era played a crucial role in ensuring the well-being of both mothers and babies during childbirth.

Birthing

Childbirth in Ming Era China was a significant event that involved a combination of traditional practices and cultural beliefs. Expectant mothers would typically rely on the assistance of experienced midwives, who provided support and guidance throughout the entire process. Women usually took vertical positions during delivery and were most likely supported under the arms by midwives. The Ming era saw the use of various techniques to aid in labor, including herbal remedies, acupuncture, and massage. Midwives would monitor the progress of labor, ensuring the safety and well-being of both mother and baby, and ritual techniques and manual manipulations were applied to solve complications such as breech birth. After the birth, attention would be given to the newborn, including cleaning, swaddling, and providing postnatal care. The birthing practices of the Ming era reflected the importance placed on maternal and infant health and the significance of ensuring a smooth and safe delivery.

“Doing the Month”

“Doing the Month” in Ming China, also known as “Zuo Yuezi” or “Sitting the Month,” was a significant postpartum tradition. Lasting approximately 30 days, it involved new mothers observing specific customs to facilitate their recovery and bonding with the newborn. During this period, the mother followed a special diet, avoided strenuous activities, and received support from family members, particularly the maternal grandmother or mother-in-law. They provided assistance with household tasks, cared for the baby, and offered guidance on baby care and breastfeeding. This practice exemplified the cultural importance placed on postpartum care and the belief that proper rest and attention during this time would contribute to the well-being of both mother and child.

References

Article: Mulder, Tara. “Midwifery in Modern China” Medium. 12 December 2018.

Wikipedia: Childbirth in China. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Childbirth_in_China#Birth_Attendants)

Article: Callister, Lynn Clark, PhD, RN, FAAN. “Doing the Month: Chinese Postpartum Practices” MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. p. 390. November 2006.

Funerals

Ming Era funerals were elaborate and deeply rooted in Chinese cultural beliefs and traditions. The rituals and customs surrounding death and burial were considered crucial for honoring the deceased and ensuring a peaceful transition to the afterlife. The process typically began with washing and dressing the body of the deceased, which was often done by family members. The body would then be placed in a wooden coffin, accompanied by personal belongings and items believed to be necessary for the afterlife. Funeral rites involved mourning ceremonies and rituals, where family members would pay their respects, offer prayers, and burn incense.

In Ming Era China, the funeral procession was a grand and solemn affair. It involved the participation of family members, friends, and mourners, who would accompany the coffin to the burial site. The procession was often led by musicians playing funeral dirges, while family members would wear mourning clothes and walk in a specific order. The deceased’s social status and wealth could influence the scale and extravagance of the funeral procession, with high-ranking officials and nobility receiving more elaborate ceremonies.

Burial practices during the Ming Era varied depending on the social status of the deceased. The elite and nobility were often buried in elaborate tombs, carefully selected and constructed to reflect their status and wealth. These tombs were typically located in scenic areas or ancestral lands and featured intricate stonework, sculptures, and ornate decorations. Commoners, on the other hand, were more likely to be buried in simpler graves or communal burial sites. Ancestral worship and the veneration of deceased family members played a significant role in Ming Era funeral customs, as families would continue to honor and offer sacrifices to their ancestors long after the funeral rites were completed.

References

Article: Mack, Lauren. Chinese Funeral Traditions. ThoughtCo. 28 January 2020.

Article: Chinese Funeral Customs. China Culture.

Article: “A Complete Guide to Traditional Chinese Funeral Customs” Dignity Memorial.

Website: Traditional Chinese Funeral Arrangements. BuddhaNet.

Dragon Boat Festival

The Dragon Boat Festival, also known as Duanwu Festival, is a traditional Chinese holiday that has been celebrated for centuries. During the Ming Era, this festival was widely observed and followed with great enthusiasm. The festival takes place on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, which usually falls in June.

The Dragon Boat Festival has several customs and traditions associated with it. One of the most iconic elements is the dragon boat races. These races involve teams of rowers paddling in long, narrow boats decorated like dragons. The boats are accompanied by the rhythmic beat of drums and the cheering of spectators. The dragon boat races symbolize the ancient practice of searching for the body of the famous poet and statesman Qu Yuan, who drowned himself in a river as a form of protest against political corruption.

Another significant aspect of the Dragon Boat Festival is the consumption of zongzi, a traditional food made of glutinous rice wrapped in bamboo leaves. Zongzi are often filled with various ingredients such as meats, beans, and nuts, and then steamed or boiled. These delicious treats are enjoyed by people during the festival as a way to commemorate Qu Yuan and to ward off evil spirits.

During the Ming Era, people would also hang up pouches filled with medicinal herbs, known as “Xiongzhong,” on their doors or wear them as accessories. It was believed that these pouches could protect against evil spirits and diseases. Additionally, people would use herbs and other natural ingredients to ward off mosquitoes and other insects during the festival.

The Dragon Boat Festival in the Ming Era was a time of lively festivities, cultural traditions, and communal spirit. It celebrated Chinese history, honored the memory of Qu Yuan, and fostered a sense of unity and togetherness among the people. These traditions and customs continue to be observed and cherished in modern-day celebrations of the Dragon Boat Festival.

References

Article: Meredith, Anne. “The History and Modern Practice of the Dragon Boat Festival“. Chinese Language Institute (CLI). 27 March 2022.

Website: Guozhen, Yang and Liu Fang. Paintings About the Dragon Boat Festival. ChinaCulture.org.

Website: THE CHINESE DRAGON BOAT FESTIVAL. China Family Adventure.

Wikipedia: Dragon Boat Festival. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragon_Boat_Festival)

YouTube: Dragon Boat Festival. Channel: Smithsonian Folklife. 14 April 2020.

Tea in Ming China and Today

Tea has a rich and vibrant history in Ming China, where it was not only a popular beverage but also a symbol of culture and social gatherings. Tea shops played a significant role in Ming society, serving as places for people to relax, socialize, and enjoy the art of tea. These tea shops offered a wide variety of teas, each with its own unique flavors and characteristics. From delicate green teas like Longjing to bold and robust black teas like Lapsang Souchong, Ming tea culture encompassed a diverse range of flavors and aromas.

Today, we can still embrace the traditions of Ming tea culture and incorporate them into our modern lives. Tea shops continue to thrive, providing a sanctuary where people can escape the hustle and bustle of daily life and indulge in the pleasure of tea. By exploring different types of tea and learning about their origins and brewing techniques, we can deepen our appreciation for this ancient beverage. Tea tastings, similar to those held in Ming tea shops, allow us to explore the nuances of various teas and expand our palate.

To further enhance the tea experience, Bana Tea Company offers a tea tasting kit that complements the exploration of Lady Tan’s Circle of Women. The kit provides a curated selection of unique teas, allowing book groups and singles to immerse themselves in the flavors. By engaging in tea tastings and learning about the cultural significance of tea, we can connect with the past while enjoying the timeless pleasure of tea in the present.