Discover Lady Tan’s World

Use the tabs to navigate through the Lady Tan’s World.

Part 1: Lady Tan and Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Tan Yunxian

- Traditional Chinese Medicine

- The Four Examinations

- The Five Depot Organs

- The Five Elements

- Pulse-taking

- Traditional Chinese Medicinal Herbs

- Angelica

- Atractylodis

- Forsythia

- Ginseng

- Honey Locust Fruit

- Licorice Root

- Lovage

- Mugwort

- Poria Mushroom

- Radish Seeds

- Rehmannia

- White Peony Root

- Moxibustion

- Small Pox and Variolation

Part 2: Historical Ming China

- Ming Dynasty

- History of the Ming Dynasty

- Traditional Hanfu

- Makeup and Hair

- Imperial Scholars

- Imperial Exams

- Civil Badges

- Military Badges

Part 3: Traditions and Culture

- Marriage Bed

- Confucius

- Forensics and Punishments

- The Washing Away of Wrongs

- Cangue

- Punishments and Tortures

- Foot Binding

- Concubines and Eunuchs

- Concubines

- Eunuchs

- Weddings

- Wedding Costume and Headdress

- Three Letters

- Six Etiquettes

- Child Bearing

- Midwives

- Childbirth

- Funerals

- Dragon Boat Festival

- Tea

Part 4: People and Places

- Garden of Fragrant Delights

- Humble Administrator’s Garden

- Qiao’s Family Compound

- Places

- Grand Canal

- Sampan

- Wuxi

- Lake Tai

- Forbidden City

- People

- Emperor Hongzhi

- Empress Zhang

Historical Ming Dynasty

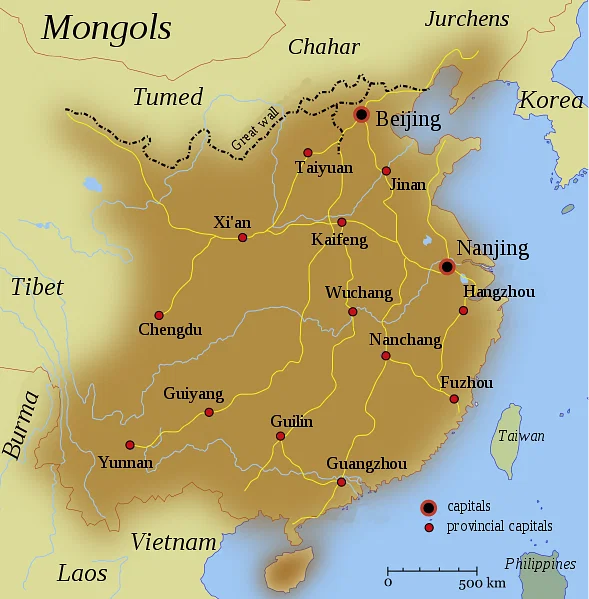

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was a remarkable period in Chinese history known for its cultural and technological achievements. Following the collapse of the Yuan Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty emerged as a beacon of cultural restoration and preservation. It embraced traditional Chinese values, fostering a renaissance of art, literature, and porcelain production. Notably, the dynasty saw advancements in technology and exploration, with Admiral Zheng He leading maritime expeditions that showcased China’s naval power and expanded its influence.

The Ming Dynasty also introduced significant administrative and social reforms. The imperial examination system, which selected officials based on merit rather than birth, underwent refinement, providing opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds to serve in government. These reforms fostered social mobility and intellectual growth. In the upcoming sections, we will delve into the captivating details of Ming Dynasty culture, including fashion, hairstyles, makeup, the esteemed imperial scholars, and the rigorous imperial examinations that shaped governance. Click the topics below to enjoy an enthralling journey through one of China’s most illustrious dynasties.

Pick a Topic below for more info.

Ming Dynasty History Overview

The Ming Dynasty, established in 1368, marked a significant turning point in Chinese history. It emerged after the overthrow of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty by Zhu Yuanzhang, a peasant who later became Emperor Hongwu. Zhu Yuanzhang’s rise to power came amidst a backdrop of social unrest and economic hardships caused by years of Mongol rule. With a vision to restore traditional Chinese values and reclaim the “Middle Kingdom,” he established the Ming Dynasty with its capital at Nanjing.

Under the Ming Dynasty, China experienced a period of stability, economic growth, and cultural renaissance. The Ming emperors implemented a series of reforms aimed at consolidating their rule and improving governance. They strengthened central authority, reestablished the civil service examination system, and promoted Confucianism as the dominant ideology. Emperor Yongle, in particular, played a pivotal role in expanding China’s influence through naval expeditions led by Admiral Zheng He, showcasing China’s advanced maritime technology and establishing diplomatic relations with other nations.

Illustration © Michal Klajban

05 Feb 2019

The Ming Dynasty is renowned for its achievements in art, literature, and science. The era witnessed a flourishing of traditional Chinese culture, with notable advancements in painting, calligraphy, poetry, and ceramics. Ming artisans produced exquisite porcelain known as “blue and white” ware, characterized by its cobalt blue designs on a white background. The construction of the iconic Forbidden City in Beijing, a grand imperial palace complex, stands as a testament to the dynasty’s architectural prowess.

International trade played a significant role during the Ming Dynasty. China actively engaged in maritime commerce and diplomacy, particularly during the early years of the dynasty. The voyages of Zheng He’s fleet brought China’s influence to distant lands, establishing trade networks and showcasing China’s wealth and power. These expeditions fostered cultural exchanges and diplomatic ties with countries in Southeast Asia, India, and Africa. However, as the dynasty progressed, Ming rulers adopted a more isolationist policy, restricting maritime activities and focusing on internal stability.

The Ming Dynasty’s international trade was not limited to maritime routes alone. Overland trade routes such as the Silk Road continued to connect China with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Chinese goods, particularly silk, porcelain, and tea, were highly sought after in the global market, contributing to China’s economic prosperity. The Ming Dynasty’s trade policies promoted economic growth and cultural exchanges, leaving a lasting impact on the development of world trade.

Throughout its nearly three-century reign, the Ming Dynasty left an indelible mark on Chinese history. Its accomplishments in governance, culture, and international trade shaped the course of Chinese civilization. Be sure to click on all the tabs as we delve further into the fascinating details of Ming Dynasty society, including clothing, hair and makeup, and the imperial scholars and the rigorous exams.

Go read this fascinating article: Cartwright, Mark. Ming Dynasty. World History Encyclopedia. 6 Feb 2019.

Hanfu Clothing

Hanfu, the traditional clothing of the Han ethnic group in China, underwent significant transformations during the Ming Dynasty. The Ming Dynasty Hanfu was characterized by its elegance, refinement, and adherence to traditional Chinese aesthetics. The clothing styles during this period were influenced by the revival of ancient Chinese culture and the desire to reclaim traditional customs and values.

One of the notable features of Ming Dynasty Hanfu was its distinct layering and voluminous silhouette. Men typically wore a robe that featured wide sleeves and a loose fit, often accompanied by a long gown or a cross-collar robe known as ruqun. The garments were made from luxurious fabrics such as silk, adorned with intricate embroidery, and embellished with auspicious symbols and patterns.

For women, Ming Dynasty Hanfu showcased a variety of styles and designs. The ruqun remained a popular choice, consisting of a long, pleated skirt paired with a top or a jacket. Women also wore qixiong ruqun a two-piece ensemble with a form-fitting bodice and a long skirt. The clothing was typically embellished with delicate embroidery, vibrant colors, and exquisite accessories like headdresses and hairpins.

The Ming Dynasty Hanfu reflected the social status and occasions of the wearer, with different styles for everyday wear, formal occasions, and ceremonial events. The clothing not only served as a form of self-expression but also conveyed cultural identity and societal norms. Today, there is a growing interest in reviving and preserving the beauty and elegance of Ming Dynasty Hanfu, with enthusiasts and scholars exploring its historical significance and promoting its revival as a cherished aspect of Chinese cultural heritage.

Makeup, Hair Styles and Ornaments

During the Ming Dynasty, hairstyles, hair ornaments, and makeup played an important role in defining one’s social status, fashion sense, and cultural identity. Both men and women paid great attention to their hairstyles and adorned them with various accessories.

In terms of hairstyles, men during the Ming Dynasty typically wore their hair long and tied it up in a topknot or a bun at the back of the head. The hairstyle was often secured with a decorative hairpin or a silk ribbon. The style and positioning of the topknot could vary depending on one’s social status and occupation.

For women, the Ming Dynasty hairstyles were more elaborate and intricate. Women often wore their hair in various styles such as braids, buns, or elaborate updos. They adorned their hairstyles with hairpins, combs, and other hair ornaments made of precious materials like gold, silver, jade, or pearls. These hair ornaments were often intricately crafted and embellished with colorful gemstones or intricate designs.

In terms of makeup, women during the Ming Dynasty favored a pale complexion. They used rice powder or white lead-based cosmetics to achieve a fair and porcelain-like skin tone. Darkened eyebrows were considered fashionable, and women used various techniques such as applying soot or using ink to darken and shape their eyebrows. They also applied rouge or blush to their cheeks and tinted their lips with natural dyes.

It’s important to note that while these were general trends, specific hairstyles, hair ornaments, and makeup practices could vary depending on factors such as social status, age, and regional customs within the Ming Dynasty.

Imperial Scholars

“The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (Chinese: 士大夫; pinyin: shì dàfū), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

“Scholar-officials were politicians and government officials appointed by the emperor of China to perform day-to-day political duties from the Han dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, China’s last imperial dynasty. After the Sui dynasty these officials mostly came from the scholar-gentry (紳士 shēnshì) who had earned academic degrees (such as xiucai, juren, or jinshi) by passing the imperial examinations. Scholar-officials were the elite class of imperial China. They were highly educated, especially in literature and the arts, including calligraphy and Confucian texts. They dominated the government administration and local life of China until the early 20th century.” [Wikipedia: Imperial Scholars]

Imperial Exams

The imperial examination system, known as “keju” in Chinese, was a civil-service examination system implemented during Imperial China with the purpose of selecting individuals for government positions. Under the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE), the civil service exams were fully revived and introduced certain refinements to the system used in previous dynasties.

One notable change introduced by the Ming Dynasty was the implementation of a geographical quota system. This system aimed to prevent wealthier regions from dominating all the positions in the civil service. It ensured that candidates from different regions had an opportunity to participate and contribute to the bureaucracy. Additionally, the Ming Dynasty expanded the number of schools, making education more accessible to children from families who could not afford private tutoring.

The exams were conducted every three years, starting with the provincial exams in the autumn, followed by the level two exams in major cities during the spring, and finally, the level three exams held in the imperial palace. Initially, there were no restrictions on the number of candidates, but as the number grew significantly, a limit of 300 candidates per sitting was imposed in 1475 CE. The exams consisted of various sections, with particular emphasis placed on the “jinshi” section, which carried great weight in determining a candidate’s future career prospects. Those who excelled in this section had the opportunity to secure prestigious positions in the Hanlin Academy, where important state documents were compiled and reviewed.

Passing the exams required a comprehensive understanding of Confucian texts, particularly the “Four Books,” which included the Analects of Confucius, Mencius, Great Learning, and Doctrine of the Mean. Mastery of these texts became essential for success in the exams, and their study was favored during the Ming Dynasty. The exams themselves became increasingly demanding, with multiple parts that tested not only academic knowledge but also political views. The passing rates remained relatively low, with only 2-4% of candidates passing the second level exams and 7-9% passing the third level exams during the Ming Dynasty.

It is important to note that successful candidates who passed the lowest level exam but did not pass the second level had to periodically take additional tests to maintain their status and continue their careers within the civil service.

References

Source: “Ming Dynasty Examinations” by Mark Cartwright, Ancient History Encyclopedia

Article: Cartwright, Mark. “The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China.” World History Encyclopedia. 8 Feb 2019.

Article: Theobald, Ulrich. “The Chinese Imperial Examination System.” China Knowledge.de: An Encyclopædia of Chinese History, Literature and Art. 26 Nov 2011

Wikipedia: Imperial Examinations. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_examination#Ming_dynasty)

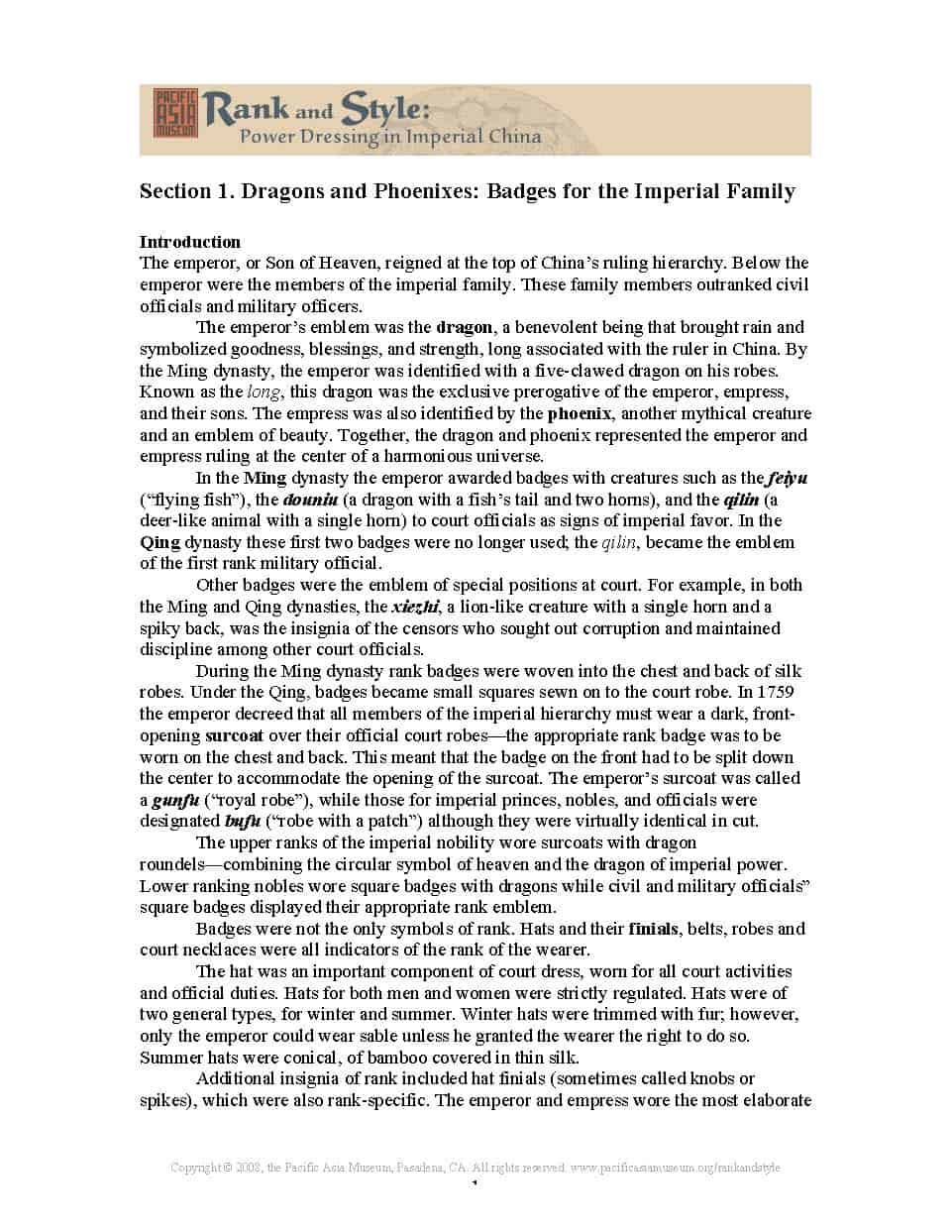

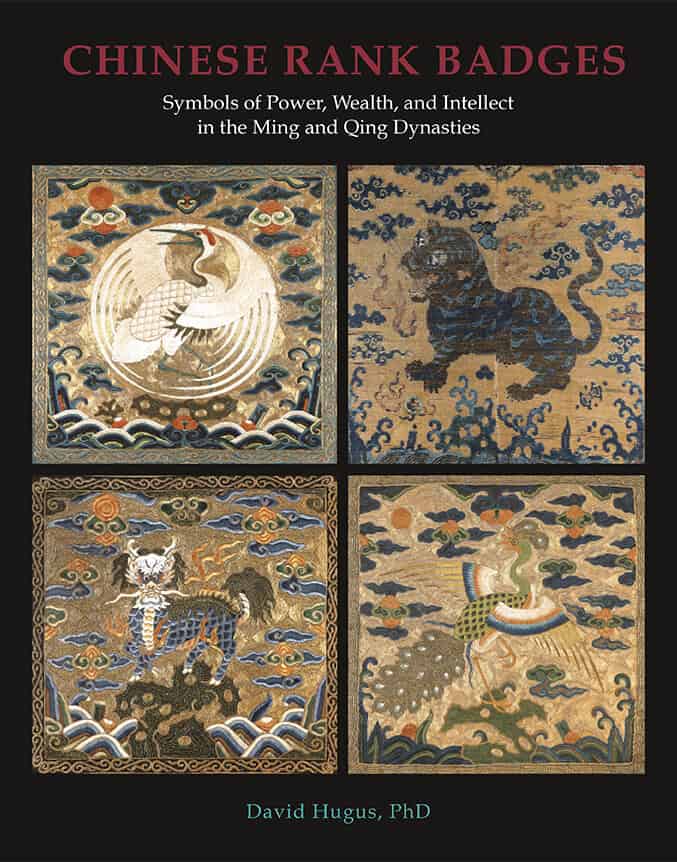

Civil Badges

A badge featuring a bird identified the wearer as a civil official. To attain such a position required years of intense study, so birds may have been selected because of their literary associations. Each rank was represented by a different species, and while there were slight variations over time, by the Qing Dynasty the order from highest to lowest was: crane, golden pheasant, peacock, wild goose, silver pheasant, egret, mandarin duck, quail and paradise flycatcher.

During the Ming Dynasty in China (1368-1644 CE), civil badges were worn by government officials as a way to show their rank and position. These badges were fabric patches with embroidered designs that varied based on the official’s authority. They were typically worn on the front and back of the official’s robe, with larger badges indicating higher ranks.

The civil badges served both a decorative and practical purpose. They showcased the craftsmanship of Ming artisans, featuring symbols like dragons and phoenixes to represent power and good fortune. Additionally, the badges helped identify officials and maintain order within the government structure. Civil officials sat on the emperor’s left at court functions, so their rank birds faced right towards him.

Wearing a civil badge without the appropriate rank was a serious offense and could lead to punishment. The Ming Dynasty placed great importance on the system of civil badges, which symbolized the hierarchical structure of the government and the significance of visual representation in the imperial bureaucracy.

(Source: “Ming Dynasty Rank Badges” by Henny Scott, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

(Source: QING-DYNASTY RANK BADGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. Umma Exchange. )

References

Source: Rank and Style: Power Dressing in Imperial China. USC Pacific Asia Museum.

Source: “Ming Dynasty Rank Badges” by Henny Scott, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source: QING-DYNASTY RANK BADGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. Umma Exchange.

Military Badges

During the Ming Dynasty in China, military badges played a significant role in distinguishing rank and promoting military discipline. These badges, known as “Buzi,” were worn by soldiers and military officials as a symbol of their status and authority within the military hierarchy.

Military badges in the Ming Dynasty were typically made of fabric or embroidered silk and featured various designs and motifs that represented the wearer’s rank, position, and achievements. The badges were often attached to the front or back of the uniform or worn on the chest or shoulders.

The designs of the badges varied depending on the military branch and rank. Generals and high-ranking officers would often have more elaborate and intricate badges, adorned with symbols of power and authority, such as dragons, mythical creatures, or auspicious motifs. Lower-ranking soldiers and officers would have simpler designs, usually featuring symbols associated with their specific unit or division.

In addition to indicating rank, military badges also served practical purposes on the battlefield. They helped soldiers identify their comrades in the midst of combat, enabling effective coordination and communication. The badges also instilled a sense of pride, camaraderie, and loyalty among the troops, reinforcing their allegiance to their commanders and the Ming Dynasty.

The use of military badges in the Ming Dynasty exemplified the strict hierarchical structure and organization of the military forces. These badges not only provided visual recognition but also served as a visual representation of the military’s power and authority. They played an essential role in maintaining order, discipline, and cohesion within the Ming Dynasty’s military ranks.

(Source: “Ming Dynasty Rank Badges” by Henny Scott, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

(Source: QING-DYNASTY RANK BADGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. Umma Exchange. )

References

Source: Rank and Style: Power Dressing in Imperial China. USC Pacific Asia Museum.

Source: “Ming Dynasty Rank Badges” by Henny Scott, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source: QING-DYNASTY RANK BADGES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN. Umma Exchange.