Historical Fiction

The Island of Sea Women

A Novel

THE ISLAND OF SEA WOMEN offers up an evocative tale of two best friends whose bonds are both strengthened and tested over decades by forces beyond their control. Set largely on the remote Korean island of Jeju, THE ISLAND OF SEA WOMEN follows Young-sook and Mi-ja, girls from strikingly different backgrounds who bond over their shared love of the sea. Working in their village’s all-female diving collective, the two friends come of age in a community where gender roles are anything but typical. Here, women are the primary breadwinners, the heads of household in all but name, and yet, as Mi-ja and Young-sook come to realize, there are limits to their control that can prove devastating.

Over the years, Young-sook and Mi-ja endure together the loss of parents, the dramas of marriage and childbirth, cruel family members, disruptive technological advances, and the ever-present dangers that accompany their livelihood. They also face growing unrest from the political turmoil that surrounds their homeland: Japanese occupation gives way to World War II, the Korean War, and its aftermath, leaving the residents of Jeju caught between warring empires. The daughter of a Japanese collaborator, Mi-ja will forever bear the mark of her father’s activities, while Young-sook looks poised to inherit her mother’s role as the leader of her village diving collective. As their husbands’ political ties and tumultuous world events threaten their friendship, Young-sook and Mi-ja see their remote island and everything they have known upended.

THE ISLAND OF SEA WOMEN deftly explores the complexities of female friendship and introduces readers to the remarkably strong and spirited female divers of Jeju Island. It’s also an eye-opening portrait of a country ravaged by decades of conflict and unrest, and a searing examination of the effects that foreign intervention can have on the evolution of a nation and of course individual lives. It asks the eternal questions: How do we find forgiveness? Can we find forgiveness? Booklist has called the novel, “A stupendous multigenerational family saga, See’s latest also provides an enthralling cultural anthropologyhighlighting the soon-to-be-lost, matriarchal haenyeo phenomenon and an engrossing history of violently tumultuous twentieth-century Korea… Stupendous…Mesmerizing.”

Buy the Book

Paperback

HARDCOVER

EBOOK

AUDIOBOOK

Praise & Reviews

“The fierce free-diving women on the Korean island of Jeju are the subject of Lisa See’s mesmerizing new historical novel that celebrates women’s strengths—and the strength of their friendships.”

—Oprahmag.com

“Lisa See excels at mining the intersection of family, friendship and history, and in her newest novel, she reaches new depths exploring the matrifocal haenyeo society in Korea, caught between tradition and modernization. This novel spans wars and generations, but at its heart is a beautifully rendered story of two women whose individual choices become inextricably tangled.”

—Jodi Picoult, NYT bestselling author of A SPARK OF LIGHT and SMALL GREAT THINGS

“A stupendous multigenerational family saga, See’s latest also provides an enthralling cultural anthropology highlighting the soon-to-be-lost, matriarchal haenyeo phenomenon and an engrossing history of violently tumultuous twentieth-century Korea. A mesmerizing achievement. See’s accomplishment, acclaim, and readership continue to rise with each book, and interest in this stellar novel will be well stoked.”

—Terry Hong, Booklist, STARRED review

“I was spellbound the moment I entered the vivid and little-known world of the diving women of Jeju. Set amid sweeping historical events,The Island of Sea Women is the extraordinary story of Young-sook and Mi-ja, of women’s daring, heartbreak, strength, and forgiveness. No one writes about female friendship, the dark and the light of it, with more insight and depth than Lisa See.”

—Sue Monk Kidd, NYT bestselling author of THE INVENTION OF WINGS and THE SECRET LIFE OF BEES.

“I loved The Island of Sea Women from the very first page. Lisa See has created an enthralling, compelling portrait of a unique culture and a turbulent time in history, but what’s really remarkable about this novel is the characters—two women whose lifelong friendship is tested during impossibly difficult times. Compelling, heart-wrenching, and beautifully written, The Island of Sea Women will plunge you into a world and a story you’ve never read before and remind you how powerful women can and must be to survive.”

—Kristin Hannah, NYT bestselling author of THE NIGHTINGALE andETHE GREAT ALONE.

Excerpt

Day 1: 2008

An old woman sits on the beach, a cushion strapped to her bottom, sorting algae that’s washed ashore. She’s used to spending time in the water, but even on land she’s vigilant to the environment around her. Jeju is her home, an island known for Three Abundances: wind, stones, and women. Today the most capricious of these—the wind—is but a gentle breeze. Not a single cloud smudges the sky. The sun warms her head, neck, and back through her bonnet and other clothing. So soothing. Her house perches on the rocky shoreline overlooking the sea. It doesn’t look like much—just two small structures made from native stone, but the location. . . Her children and grandchildren have suggested she allow them to convert the buildings into a restaurant and bar. “Oh, Granny, you’ll be rich. You’ll never have to work again.” One of her neighbors did as the younger generation asked. Now that woman’s home is a guesthouse and an Italian restaurant. On Young-sook’s beach. In her village. She will never let that happen to her house. “There isn’t enough money in all the pockets in all Korea to make me leave,” Young-sook has said many times. How could she? Her house is the nest where she hides the joy, laughter, sorrows, and regrets of her life.

She is not alone in her work on the beach. Other women around her age—in their eighties and nineties—also pick through the algae that has come to rest on the sand, putting what’s saleable in small bags and leaving the rest. Up on the walkway that separates this cove from the road, young couples—honeymooners, probably—walk hand in hand, heads together, sometimes even kissing, in front of everyone, in broad daylight. She sees a tourist family, clearly from the mainland. The children and husband are so obvious in their matching polka dot T-shirts and lime-green shorts. The wife wears the same polka dot T-shirt, but otherwise every bit of her skin is protected from the sun by long pants, sleeve guards, gloves, hat, and a cloth mask. Children from the village climb over the rocks that spill across the sand and into the sea. Soon they’re playing in the shallow depths, giggling, and challenging each other to be the first to reach the deepest rock, locate a piece of sea glass, or find a sea urchin, if they’re lucky enough to spot one. She smiles to herself. How differently life will unfurl for these young ones. . .

She also observes other people—some not even trying to hide their curiosity—who stare at her before shifting their gazes to some of the other old women on the shore today. Which granny looks the nicest? The most accessible? What those people don’t understand is that Young-sook and her friends are appraising them too. Are they scholars, journalists, or documentarians? Will they pay? Will they be knowledgeable about the haenyeo—sea women? They’ll want to take her photo. They’ll shove a microphone in her face and ask the same predictable questions: “Do you consider yourself a granny of the sea? Or do you think of yourself more like a mermaid?” “The government labels the haenyeo a cultural heritage treasure—something dying out that must be preserved, if only in memory. How does it feel to be the last of the last?” If they’re academics, they’ll want to talk about Jeju’s matrifocal culture, explaining, “It’s not a matriarchy. Rather, it’s a society focusedon women.” Then they’ll begin to probe: “Were you really in charge in your household? Did you give your husband an allowance?” Often she’ll get a young woman who’ll ask the question Young-sook’s heard discussed her entire life. “Is it better to be a man or a woman?” No matter what the inquiry, she always answers the same way: “I was the best haenyeo!” She prefers to leave it at that. When a visitor persists, Young-sook will say gruffly, “If you want to know about me, go to the Haenyeo Museum. You can see my photo. You can watch the video about me!” If they stillwon’t go… Well, then, she becomes even more direct. “Leave me alone! I have work to do!”

Her response usually depends on how her body feels. Today, the sun is bright, the water glistens, and she perceivesin her bones—even though she’s only sitting on the shore—the weightlessness of the sea, the surge that massages the aches in her muscles, the enveloping chill that cools the heat in her joints, so she allows herself to be photographed, even pushing back the brim of her bonnet so one young man can “see your face better.” She watches as he edges toward the inevitable awkward subject, until he finally arrives at his query: “Did your family suffer during the April Third Incident?”

Aigo, of course she suffered. Of course. Of course. Of course. “Everyone on Jeju Island suffered,” she answers. But that is all she will say about it. Ever. Better to tell him this is the happiest time of her life. And it is, too. She still works, but she’s not too busy to visit friends and travel. Now she can look at her great-granddaughters and think, That’s a pretty one. That’s the smartest one yet. Or, That one better marry well. Her grandchildren and great-grandchildren give her the greatest joy. Why couldn’t she have thought like that when she was younger? But she couldn’t have imagined how her life would turn out back then. She couldn’t have imagined today even in a dream.

The young man wanders off. He tries to talk to another woman, Kang Gu-ja, who’s working about ten meters away. Gu-ja, always crotchety, won’t even look up. He presses on to Gu-ja’s younger sister, Gu-sun, who yells at him. “Go away!” Young-sook snorts appreciatively.

When her small bag is full, she shakily gets to her feet and shuffles to the collection of larger bags she’s been filling. Once the small bag is emptied, she hobbles to an area of the beach untouched by the others. She settles back down, positioning her cushion beneath her. Her hands, though gnarled from work and deeply creased from years of exposure to the sun, are agile. The sound of the sea. . . The caress of warm air. . . The knowledge that she is protected by the thousands of goddesses who live on this island. . . Even Gu-sun’s colorful epithets can’t sour her mood.

Then in Young-sook’s peripheral vision she glimpses another family group. They aren’t dressed alike, and they don’t look alike. The husband is white, the wife is Korean, and the children—a small boy and a teenage girl—are mixed. Young-sook can’t help it, but seeing those half-and-half children makes her uncomfortable: the boy in shorts, a superhero T-shirt, and clunky tennis shoes, the girl in shorts that barely cover what they’re supposed to cover, earbuds plugged into her ears, and wires trailing down over her barely-there breasts. Young-sook guesses they’re Americans, and she watches warily as they approach.

“Are you Kim Young-sook?” the woman, pale and pretty, asks. When Young-sook gives a barely perceptible nod, the woman continues. “My name is Ji-young, but everyone calls me Janet.”

Young-sook tries out the name on her tongue. “Janet.”

“And this is my husband, Jim, and my children, Clara and Scott. We’re wondering if you remember my grandmother?” Janet speaks… What does she speak exactly? It’s not Korean, but it’s not the Jeju dialect either. “Her name was Mi-ja. Her family name was Han—”

“I don’t know that person.”

The softest frown crinkles the space above the bridge of the woman’s nose. “But didn’t you both live in this village?”

“I live here, but I don’t know who you’re talking about.” Young-sook’s voice comes out even sharper and louder than Gu-sun’s, causing both Kang sisters to look her way. Are you all right?

But the American woman is undeterred. “Let me show you her photograph.”

She scrounges through her satchel, pulls out a manila envelope, and paws through it until she finds what she’s been looking for. She stretches out her hand and shows Young-sook a black-and-white photograph of a girl dressed in the white bathing costume of the past. Her nipples are like a pair of octopus eyes peering out from the protection of a cave. Her hair is hidden under a matching white scarf. Her face is round, her slim arms show the definition of muscles, her legs are sturdy, and her smile is wide and unabashed.

“I’m sorry,” Young-sook says. “I don’t know her.”

“I have more photos,” the woman goes on.

As Janet once again peers into her envelope, rifling through what must be more photographs, Young-sook smiles up at the white man. “You have phone?” she asks in English, which she realizes must sound far worse than his wife’s Korean, and then holds an imaginary phone to her ear. She’s used this tactic many times to save herself from bothersome intruders. If it’s a young woman, she might say, “Before I answer your questions, I need to talk to my grandson.” If it’s a man—of any age—she’ll ask, “Are you married yet? My great-niece is lovely, and she’s in college too. I’ll have her come so the two of you can meet.” It’s amazing how many people fall for her tricks. Sure enough, the foreign man pats his pockets as he searches for his phone. He smiles. Bright white, very straight teeth, like a shark’s. But the teenage girl gets her phone out first. It’s one of those new iPhones, exactly like the ones Young-sook bought for her great-grandchildren for their birthdays this year.

Without bothering to remove her earbuds, Clara says, “Tell me the number.” The sound of her voice further ruffles Young-sook. The girl has spoken in the Jeju dialect. It’s not perfect, but it’s passable and her inflection causes goosebumps to rise along Young-sook’s arms.

She recites the number, while Clara taps the buttons on the phone. Once she’s done, she unplugs the phone and extends it to Young-sook, who feels strangely paralyzed. On impulse—it has to be impulse, right?—the girl leans over and puts the phone to Young-sook’s ear. Her touch. . . Like lava. . . A small cross on a gold chain slips out from under the girl’s T-shirt and swings in front of Young-sook’s eyes. Now she notices that the mother, Janet, wears a cross too.

The four foreigners stare at her expectantly. They think she’s going to help them. She speaks rapidly into the phone. Janet’s brow furrows once again as she tries to understand the words, but Young-sook has spoken pure Jeju, which is as different from standard Korean as French is from Japanese, or so she’s been told. Once the call is done, Clara tucks the phone in her back pocket and watches, embarrassed, as her mother starts pulling out more photographs.

“Here is my father when he was young,” Janet says, thrusting a blurry image before Young-sook’s eyes. “Do you remember him? Here’s another photo of my grandmother. It was taken on her wedding day. I was told the girl beside her is you. Won’t you please take a few minutes to talk to us?”

But Young-sook has gone back to sorting, only occasionally glancing at the photos to be polite but registering nothing on her face that would reveal the feelings of her heart.

A few minutes later, a motorcycle with a cart attached to the back comes bumping along the beach. When it reaches her, she struggles to stand. The foreign man takes her elbow to steady her. It’s been a long time since she’s been touched by someone so white, and she instinctively pulls away.

“He only wants to help,” Clara says in her childish Jeju dialect.

Young-sook watches as the strangers try to assist her grandson as he loads the bags of algae onto the flatbed. Once everything is secured, she climbs behind her grandson and wraps her arms around his waist. She nudges him with the back of her hand. “Go!” Once they’ve cleared the beach and have bounced up onto the road, she says in a softer tone, “Drive me around for a while. I don’t want them to see where I live.”

# # #

Part I

Friendship

1938

# # #

Swallowing Water Breath

April 1938

My first day of sea work started hours before sunrise when even the crows were still asleep. I dressed and made my way through the dark to our latrine. I climbed the ladder to the stone structure and positioned myself over the hole in the floor. Below, our pigs gathered, snuffling eagerly. A big stick leaned against the wall in the corner in case one of them became too enthusiastic and tried to leap up. Yesterday I’d had to hit one pretty hard. They must have remembered, because this morning they waited for my private business to drop to the ground to fight among themselves for it. I returned to the house, tied my baby brother to my back, and went outside to draw water from the village well. Three roundtrips, carrying earthenware jugs in my hands, were required to get enough water to satisfy our morning needs. Next, I gathered dung to burn for heating and cooking. This also had to be done early, because I had a lot of competition from other women and girls in the village. My chores done, my baby brother and I headed home.

Three generations of my family lived within the same fence—with Mother, Father, and us children in the big house and Grandmother in the little house across the courtyard. Both houses were built from stone and had thatch roofs weighed down with additional stones to keep the island wind from blowing them away. The big house had three rooms: a kitchen, the main room, and a special room for women to use on their wedding nights and after they’d given birth. In the main room, oil lamps flickered and sputtered. Our sleeping mats had already been folded and stacked against the wall.

Grandmother was awake, dressed, and drinking hot water. Her hair was covered by a scarf. Her face and hands were bony and the color of chestnuts. My first and second brothers, twelve and ten years old, sat cross-legged on the floor, knees touching. Across from them, Third Brother squirmed as only a seven-year-old boy can. My little sister, six years younger than I was, helped our mother pack three baskets. Mother’s face was set in concentration as she checked and double-checked that she had everything, while Little Sister tried to show she was already training to be a good haenyeo.

Father ladled the thin millet soup that he’d prepared into bowls. I loved him. He had Grandmother’s narrow face. His long, tapered hands were soft. His eyes were deep and warm. His callused feet were almost always bare. He wore his favorite dog-fur hat pulled down over his ears and many layers of clothes, which helped to disguise how he sacrificed food, so his children could eat more. Mother, never wasting a moment, joined us on the floor and nursed my baby brother, who was barely a month old, as she ate. As soon as she was done with her soup and the feeding, she handed the baby to my father. Like all haenyeo husbands, he would spend the rest of the day under the village tree in Hado’s central square with other fathers. Together, they’d look after babies and young children. Satisfied that Fourth Brother was content in Father’s arms, Mother motioned for me to hurry. Anxiety rattled through me. I so hoped to prove myself today.

The sky was just beginning to turn pink when Mother, Grandmother, and I stepped outside. Now that it was light, I could see my steamy breath billowing then dissipating in the cold air. Grandmother moved slowly, but Mother had efficiency in every step and gesture. Her legs and arms were strong. Her basket was on her back, and she helped me with mine, securing the straps. Here I was, going to work, helping to feed and care for my family, and becoming a part of the long tradition of sea women. Suddenly I felt like a woman.

Mother hoisted the third basket, holding it before her, and together we stepped through the opening in the stone wall that protected our small piece of property from prying eyes and the relentless wind. We wended our way through the olle—one of thousands of stone-walled pathways that ran between houses and also gave us routes to crisscross the island. We stayed alert for Japanese soldiers. Korea had now been a Japanese colony for twenty-eight years. We hated the Japanese, and they hated us. They were cruel. They stole food. Inland, they rustled livestock. They took and took and took. They’d killed Grandmother’s parents, and she called them chokpari—cloven-footed ones. Mother always said that if I was ever alone and saw colonists, whether soldiers or civilians, I should run and hide, because they’d ruined many girls on Jeju.

We came around a corner and into a long straightaway. Ahead in the distance, my friend Mi-ja danced from foot to foot, to keep warm, from excitement. Her skin was perfect, and the morning light glowed on her cheeks. I’d grown up in the Gul-dong section of Hado, while Mi-ja lived in the Sut-dong section, and the two of us always met in this spot. Even before we reached her, she bowed deeply to show her gratitude and humility to my mother, who bent at her waist just enough to acknowledge Mi-ja’s deference. Then Mother wordlessly strapped the third basket to Mi-ja’s back.

“You girls learned to swim together,” Mother said. “You’ve watched and learned as apprentices. You, Mi-ja, have worked especially hard.”

I didn’t mind that Mother singled out Mi-ja. She’d earned it.

“I can never thank you enough.” Mi-ja’s voice was as delicate as flower petals. “You have been a mother to me, and I will always be grateful.”

“You are another daughter to me,” Mother replied. “Today, Halmang Samseung’s job is done. As the goddess who oversees pregnancy, childbirth, and raising a child to the age of fifteen, she is now fully released from her duties. Many girls have friends, but the two of you are closer than friends. You are like sisters, and I expect you to take care of each other today and every day as those tied by blood would do.”

It was as much a blessing as a warning.

Mi-ja was the first to voice her fears. “I understand about swallowing water breath before going beneath the waves. I must hold as much air within me as possible. But what if I don’t know when to come up? What if I can’t make a good sumbisori?”

Swallowing water breath is the process all haenyeo use to gather enough air in their lungs to sustain them as they submerge. The sumbisori is the special sound—like a whistle or a dolphin’s call—a haenyeo makes as she breaches the surface of the sea, releases the air she’s held in her lungs, followed by a deep intake of breath.

“Sucking in air shouldn’t be troublesome,” Mother said. “You breathe in every day as you walk about the earth.”

“But what if I run out of it in the watery depths?” Mi-ja asked.

“Breathing in, breathing out. Every beginning haenyeo worries about this,” Grandmother blurted before my mother could answer. She could be impatient with Mi-ja.

“Your body will know what to do,” Mother said reassuringly. “And even if it doesn’t, I will be there with you. I’m responsible for every woman’s safe return to shore. I listen for the sumbisori of all woman in our collective. Together our sumbisori create a song of the air and wind on Jeju. Our sumbisori is the innermost sound of the world. It connects you to the future and the past. A single sumbisori allows girls like you to serve her parents and then her children.”

I found this comforting, but I also became aware of Mi-ja staring at me expectantly. Yesterday we’d agreed to tell my mother of our worries. Mi-ja had volunteered hers, but I was hesitant about revealing mine. There were many ways to die in the sea, and I was scared. My mother may have said that Mi-ja was like a daughter—and I loved her for loving my friend—but I was an actual daughter, and I didn’t want her to see me as less than Mi-ja.

I was saved from having to say anything when Mother started walking. Mi-ja and I trailed after her, with Grandmother following us. We passed house after house—all made of stone with thatch roofs. The main square was deserted except for women, who were being pulled to the sea by the scent of salt air and the sound of waves. Just before reaching the beach, we stopped to pick a handful of leaves from a bank of wild mugwort, which we tucked into our baskets. We turned another corner and reached the shore. We stepped over sharp rocks, making our way to the bulteok—the fire space. It was a round, roofless structure made of stacked lava rocks. Instead of a door, two curved walls overlapped to prevent those outside from seeing in. A similar structure sat in the shallows. This was where people bathed and washed their clothes. And just offshore, where the water reached no higher than our knees, was an area walled with stone, where anchovies washed in at high tide, were trapped at low tide, and then we waded through with nets to catch them.

We had seven bulteoks in Hado—one for each neighborhood’s diving collective. Our group had thirty members. Logic would say that the entrance should face the sea, since haenyeo go back and forth from it all day, but having the entrance at the back gave an added barrier against the constant winds blowing in from the water. Above the crash of waves, we could hear women’s voices—teasing, laughing, and shouting well-worn jibes back and forth. As we entered, the gathered women turned to see who’d arrived. They all wore padded jackets and trousers.

Mi-ja set down her basket and hurried to the fire.

“No need for you to worry about tending the fire now,” Yang Do-saeng called out good-naturedly. She had high cheek bones and sharp elbows. She was the only person I knew who kept her hair in braids at all times. She was a little older than my mother, and they were diving partners and best friends. Do-saeng’s husband had given her one son and one daughter, and that was the end. A sadness, to be sure. Nevertheless, our two families were very close, especially since Do-saeng’s husband was in Japan doing factory work. These days about a quarter of all Jeju people lived in Japan, because a ferry ticket cost half the price of a single bag of rice here on our island. Do-saeng’s husband had been in Hiroshima for so many years that I didn’t remember him. My mother helped Do-saeng with ancestor worship and Do-saeng helped my mother when she had to cook for our family when we performed our rites. “You’re no longer an apprentice. You’ll be with us today. Are you ready, girl?”

“Yes, Auntie,” Mi-ja responded, using the honorific, bowing and backing away.

The other women laughed, causing Mi-ja to blush.

“Stop teasing her,” my mother said. “These two have enough to worry about today.”

As chief of this collective, Mother sat with her back against the part of the stone wall that had the best protection from the wind. Once she was settled, the other women took spots in strict order, according to her level of diving skill. The grandmother-divers—those like my mother, who’d achieved top status in the sea even if they had yet to become grandmothers on dry land—had the best seats. The actual grandmothers, like mine, didn’t have a label. They were true grandmothers, who should be treated with respect. Although long retired from sea work, they enjoyed the companionship of the women with whom they’d spent most of their lives. Now Grandmother and her friends liked to sort seaweed that had been washed ashore by the wind or dive close to the beach in the shallows, so they could spend the day trading jokes and sharing miseries. As women of respect and honor, they had the second most important seats in the bulteok. Next came the small-divers, in their twenties and early thirties, who were still perfecting their skills. Mi-ja and I sat with the baby-divers: the two Kang sisters, Gu-ja and Gu-sun, who were two and three years older than we were, and Do-saeng’s daughter, Yu-ri, who was already nineteen. The three of them had a couple years diving experience, while Mi-ja and I were true beginners, but the five of us were ranked the lowest in the collective, which meant that our seats were by the bulteok’s opening. The cold wind swirled around us, and Mi-ja and I scooted closer to the fire. It was important to warm up as best we could before entering the sea.

Mother began the meeting by asking, “Does this beach have any food?”

“More food than there are grains of sand on Jeju,” Do-saeng trilled, “if we had an abundance of sand instead of rocks.”

“More food than on twenty moons,” another woman declared, “if there were twenty moons above us.”

“More food than in fifty jars at my grandmother’s house,” a woman, who’d been widowed too young, joined in, “if she’d had fifty jars.”

“Good,” Mother said in response to the ritual bantering. “Then let us discuss where we will dive today.” At home, her voice always seemed so loud. Here, hers was just one of many loud voices, since the ears of all haenyeo are damaged over time by water pressure. One day I too would have a loud voice.

The sea doesn’t belong to anyone, but every seaside village had assigned diving rights to specific territories: close enough to the shore to walk in, within twenty- to thirty-minutes-swimming distance from land, or accessible only by boat farther out to sea; a cove here, an underwater plateau not too far offshore, the north side of this or that island, and so on. Mi-ja and I listened as the women considered the possibilities. As baby-divers, we hadn’t earned the right to speak. Even the small-divers kept quiet. Mother struck down most proposals. “That area is over-fished,” she told Do-saeng. Another time, she came back with “Just as on land, our sea fields also follow the seasons. To honor spawning times, conch can’t be picked from the ocean floor from July to September, and abalone can’t be harvested from October through December. It is our duty to be keepers and managers of the sea. If we protect our wet fields, they will continue to provide for us.” Finally, she made her decision. “We’ll row to our underwater canyon not far from here.”

“The baby-divers aren’t ready for that,” one of the grandmother-divers said. “They aren’t strong enough, and they haven’t earned the right either.”

Mother held up a hand. “In that area, lava flowed from Grandmother Seolmundae to form the rocky canyon. Its walls provide something for every ability. The most experienced among us can go as deep as we want, while the baby-divers can pick through those spots close to the surface. The Kang sisters will show Mi-ja what to do. And I’d like Do-saeng’s daughter, Yu-ri, to watch over Young-sook. Yu-ri will soon become a small-diver, so this will be good training for her.”

Once Mother explained, there were no further objections. Mothers are closer to the women in their diving collective than they are to their own children. Today, my mother and I had begun to form that deeper relationship. Observing Do-saeng and Yu-ri together, I could see where my mother and I would be in a few years. But this moment also showed me why Mother had been elected chief. She was a leader, and her judgment was valued.

“Every woman who enters the sea carries a coffin on her back,” she warned the gathering. “In this world, in the undersea world, we tow the burdens of a hard life. We are crossing between life and death every day.”

These traditional words were often repeated on Jeju, but we all nodded somberly as though hearing them for the first time.

“When we go to the sea, we share the work and the danger,” Mother added. “We harvest together, sort together, and sell together, because the sea itself is communal.”

With that final rule stated—as though anyone could forget something so basic—she clapped her hands twice on her thighs to signal that the meeting had ended and we needed to get moving. As my grandmother and her friends filed outside to work on the shore, Mother motioned to Yu-ri to help me get ready. Yu-ri and I had known each other our entire lives, so naturally we were a good match. The Kang sisters didn’t know Mi-ja well and probably wanted to keep their distance from her. She was an orphan, and her father had been a collaborator, working for the Japanese in Jeju City. But whether or not the Kangs liked it, they had to do what my mother ordered.

“Stand close to the fire,” Yu-ri told me. “The faster you get undressed and ready, the faster we’ll be in the water. The sooner we go into the water, the sooner we’ll return here. Now, follow what I do.”

We edged closer to the flames and stripped off our clothes. No one showed any inhibitions. This was like being together in the communal bath. Some of the younger women were big with babies growing in their bellies. Older women had stretch marks. Even older women had breasts that sagged from too much living and giving. Mi-ja’s and my bodies showed our age too. We were fifteen years old, but the harshness of our environment—little food, hard physical work, and cold weather—meant that we were as skinny as eels, our breasts had not yet begun to grow, and just a few wisps of hair showed between our legs. We stood there, shivering, as Yu-ri, Gu-ja, and Gu-sun helped us put on our three-piece water clothes made from plain white cotton. The white color would make us more visible underwater, and it was said to repel sharks and dolphins, but, I realized, the thinness of the fabric would do little to keep us warm.

“Pretend Mi-ja is a baby,” Yu-ri told the Kang sisters, “and tie her into her suit.” Then to me, she explained, “You can see that the sides are open. You fasten them together with the ties. This allows the suit to tighten or expand with pregnancy or other types of weight gain or loss.” She leaned in. “I long for the day when I can tell my mother-in-law that my husband has put a baby in me. It will be a son. I’m sure of it. When I die, he’ll perform ancestor worship for me.”

Yu-ri’s wedding was set for the following month, and of course she was dreaming of the son she would have, but her sense of anticipation seemed unimportant to me right then. Her fingers felt icy against my skin, and goose bumps rose on my flesh. Even after she’d tied the laces as tight as possible, the suit still bagged on me. Same on Mi-ja. These suits have forever marked the haenyeo as immodest, for no proper Korean woman, whether on the mainland or here on our island, would ever bare so much skin.

The whole time, Yu-ri continued talking, talking, talking. “My brother is very smart, and he works hard in school.” My mother may have been the head of the collective, but Do-saeng had a son who was the pride of every family in Hado. “Everyone says Jun-bu will go to Japan to study one day.”

Jun-bu was the only son, and the gift of education was bestowed on him alone. Yu-ri and her father contributed to the family’s income, although they still didn’t earn as much as Do-saeng, while my mother had to raise all the money to send my brothers to school without help from my father. They would be lucky to go beyond elementary school.

“I’ll need to work extra hard to help pay for Jun-bu’s tuition andhelp my new family.” Yu-ri called across the room to her mother and future mother-in-law. “I’m a good worker, eh?” Yu-ri was known throughout our village as a chatterbox. She seemed worry free, and she was a good worker, which was why it had been easy to find a match for her.

She turned her attention back to me. “If your parents love you greatly, they’ll arrange a marriage for you right here in Hado. You’ll maintain your diving rights, and you’ll be able to see your natal family every day.” Then realizing what she’d said, she tapped Mi-ja’s arm. “I’m sorry. I forgot you don’t have parents.” She didn’t think long enough before she spoke again. “How are you going to find a husband?” she asked with genuine curiosity.

I glanced at Mi-ja, hoping she hadn’t been hurt by Yu-ri’s thoughtlessness, but her face was set in concentration as she tried to follow the Kang sisters’ instructions.

Once we had on our suits, we put on water jackets. These were for cold weather only, but I couldn’t see how, since they were the same thin cotton as the rest of the outfit. Last, we tied white kerchiefs over our hair to conserve body heat and because no one would wish for a loose tendril to get tangled in seaweed or caught on a rock.

“Here,” Yu-ri said, pressing paper packets filled with white powder into our hands. “Eat this, and it will help prevent diving sickness—dizziness, headaches, and other pains. Ringing in the ears!” Yu-ri scrunched up her face at the thought. “I’m still a baby-diver, and I already have it. Ngggggg—” She imitated the high-pitched sound that apparently buzzed in her head.

Following the example of Yu-ri and the Kang sisters, Mi-ja and I unfolded the paper packets, tilted our heads back like baby birds, poured the bitter-tasting white powder into our mouths, and swallowed. Then Mi-ja and I watched as the others spit on their knives to bring good luck in finding and harvesting an abalone—a prized catch, for each one fetched a great price.

Mother checked to make sure I had all my gear. She focused particularly on my tewak—a hollowed out gourd that had been left to dry in the sun, which would serve as my buoy. She then did the same with Mi-ja. We each had a bitchang to use for prying creatures from their homes and a pronged hoe to pick between the cracks and embed in the sand or on a crag to help pull us from place to place. We also had a sickle for cutting seaweed, a knife for opening sea urchins, and a spear for protection. Mi-ja and I had used these tools for practice while playing in the shallows, but Mother made a point to say, “Don’t use these today. Just get accustomed to the waters around you. Stay aware of your surroundings, because everything will look different.”

Together we left the bulteok. We’d return several hours later to store and repair our equipment, measure the day’s harvest, divvy up the proceeds, and, most important, warm up again. We might even cook and share a little of what we’d brought back in our nets, if the harvest was bountiful. I looked forward to it all.

As the other women boarded the boat, Mi-ja and I lingered on the jetty. She rummaged through her basket and pulled out a book, while I brought out a piece of charcoal from my basket. She ripped a page from the book and held it over the written character name for the boat. Even tied up, it bobbed in the waves, making it nearly impossible for Mi-ja to keep the paper steady and for me to rub it with the charcoal. Once I was done, we took a moment to examine the result: a shadowy image of a character we couldn’t read but knew meant Sunrise. We’d been commemorating our favorite moments and places this way for years. This wasn’t our best rubbing, but with it we’d remember this day forever.

“Hurry along,” Mother called down to us, tolerant but only up to a point.

Mi-ja tucked the paper back in the book to keep it safe, then we scrambled aboard and took up oars. As we slowly rowed away from the jetty, my mother led us in song.

“Let us dive.” Her gravelly voice cut through the wind to reach my ears.

“Let us dive,” we sang back to her, our rowing matching the rhythm of the melody.

“Golden shells and silver abalones,” she sang.

“Let us get them all!” we responded.

“To treat my lover. . .”

“When he comes home.”

I couldn’t help but blush. My mother didn’t have a lover, but this was a much-beloved song and all the women liked it.

The tide was right, and the sea was relatively calm. Still, despite the rowing and singing, I began to feel sick to my stomach and Mi-ja’s usually pink cheeks turned an ashen gray. We brought up our oars when we reached the diving spot. The boat dipped and swayed in the light chop. I attached my bitchang to my wrist and grabbed my net and tewak. A light wind blew, and I began to shiver. I was feeling pretty miserable.

“For a thousand years, for ten thousand years, I pray to the Dragon Sea God,” Mother called out across the waves. “Please, ocean king spirit, no strong winds. Please no strong currents.” She poured offerings of rice and rice wine into the water. With the ritual completed, we wiped the insides of our goggles with the mugwort we’d picked to keep them from fogging up and then positioned them over our eyes. Mother counted as each woman jumped into the water and swam away in twos and threes. With fewer women onboard to help weigh down the boat, it rocked even worse. Yu-ri steadied herself before finally leaping over a swell and into the water. The Kang sisters held hands when they jumped. Those two were inseparable. I hoped their loyalty would now expand to include Mi-ja, and they’d watch out for her in the same way they did each other.

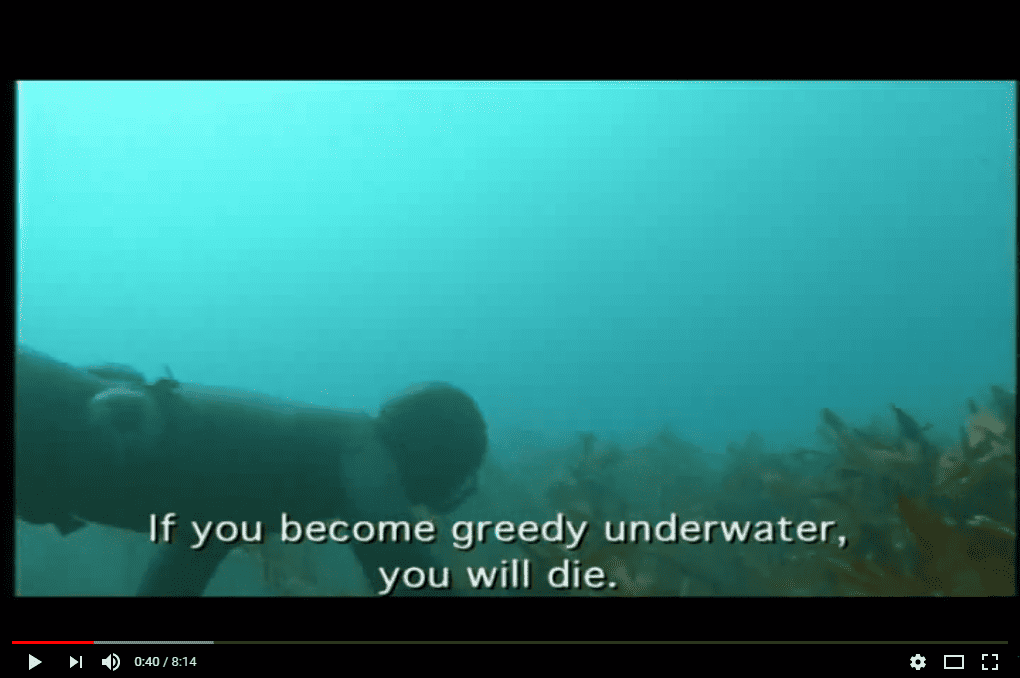

Mother gave some final advice: “The sea, it is said, is like a mother. The saltwater, the pulse and surges of the current, the magnified beat of your heart, and the muffled sounds reverberating through the water together recall the womb. But for us haenyeo we must always think about making money. . . and surviving. Do you understand?” When we nodded, she went on. “This is your first day. Don’t be greedy. If you see an octopus, ignore it. A haenyeo must learn how to knock out an octopus underwater, or else it could use its arms against you. And stay away from abalone too!”

She didn’t have to explain more. It can take months before a beginning haenyeo is ready to risk prying an abalone from a rock. Left alone, the creature floats its shell off a rock, so that the sea’s nourishing waters can flow in and around it. When surprised—even if it’s only by the shift in current caused by a large fish swimming past—it will clamp itself to a rock so that the hard shell protects the creature inside from all predators. As a result, an abalone must be approached carefully and the tip of the bitchang inserted under the shell and flipped off the rock in one swift movement before the abalone can clamp down on the tool attached to a diver’s wrist, thereby anchoring her to the rock. Only years of experience can teach a woman how to get loose and still have enough time leftover to reach the surface for air. I was in no hurry to attempt such a hazardous activity.

“Today you follow in my wake as I once followed in my mother’s wake,” Mother went on, “and as one day your daughters will follow in your wakes. You are baby-divers. Don’t reach beyond your abilities.”

With that blessing—and warning—Mi-ja took my hand and together we jumped feet first into the water. Instant, shocking cold. I hung onto my buoy, my legs kicking back and forth beneath me. Mi-ja and I looked into each other’s eyes. It was time for swallowing water breath. Together we took a breath, a breath, a breath, filling our lungs to capacity, expanding our chests. Then we went down. Light filtered turquoise and glittery close to the surface. Around us, others shot down—with their heads directed to the ocean floor—through the canyon Mother had described, their feet pointed to the sky. Those women were quick and powerful, going down a body length, another body length, deeper and deeper into darker blue water. Mi-ja and I struggled to achieve that straight angle. For me, the worst part was my goggles. The metal frames, responding to the water pressure even at this shallow depth, cut into my flesh. They also limited my peripheral vision, creating yet another danger and forcing me to be even more vigilant in this ghostly environment.

As baby-divers, Yu-ri, the Kangs, Mi-ja, and I could only go down about two body lengths, but I watched as my mother disappeared into the inky chasm of the canyon. I’d always heard she could go down twenty and sometimes more meters on a single breath, but already my lungs burned and my heart thumped in my ears. I kicked to go up, my lungs feeling like they were about to explode. As soon as I broke the surface, my sumbisori erupted and scattered on the air. It sounded like a deep sigh—aaah—and I realized it was just as Mother had always said it would be. My sumbisori was unique. And so was Mi-ja’s, which I learned when she split the water beside me. Wheeee. We grinned at each other, then swallowed more water breath and dove down again. Nature told me what to do. The next time I surfaced, I had a sea urchin in my hand. My first catch! I put it in the net attached to my tewak, took another series of deep breathes, and went back down. I stayed within sight of Yu-ri, even if we resurfaced at different times. Every time I looked for Mi-ja, I found her not more than a meter away from one of the Kang sisters, who themselves stayed close together.

We repeated this pattern, pausing occasionally to rest on our buoys, until it was time to return to the boat. When I reached it, I easily hoisted my net—noticeably light compared to those of others—and carried it across the deck so that the woman behind me and her catch could board. Mother oversaw everything and everyone. One group of women secured their nets, tying the tops so nothing precious could escape, while Do-saeng and some others gathered around the brazier, sending warmth into their bones, drinking tea, and bragging about what they’d caught. Four stragglers still paddled toward the boat. I could sense Mother counting to make sure everyone was safe.

Yu-ri giggled at our shivering, telling us that eventually we’d get used to being cold all the time. “Four years ago, I was just like you, and now look at me,” she boasted.

It was a beautiful day, and everything had gone perfectly. I felt proud of myself. But now that the swells were rising, and the dipping and swaying of the boat was getting increasingly worse, all I wanted to do was go home. Not possible. Once our arms and legs were rosy with heat, we went back in the water. The five baby-divers stayed together—with one or another of us popping back up for air. Never before had I concentrated so hard—on my form, on the beating of my heart, on the pressure on my lungs, on looking. I can’t say that either Mi-ja or I found many sea creatures. Our main goal was not to embarrass ourselves as we tried to perfect the head-down dive position. We were pathetic. Acquiring that skill would take time.

When Mother sounded the call that the day was done and it was time to go back to shore, I was relieved. She looked in my direction, but I wasn’t sure if she saw me or not. I glimpsed Mi-ja and the Kangs swimming to the boat. They’d be the first three onboard, so they’d get to listen as the other women breached the waters and let out their sumbisori. I was about to start paddling, when Yu-ri said, “Wait. I saw something on my last dive. Let’s go get it.” She glanced around, taking in how far the grandmother-divers were from the boat. “We can do it before they get here. Come on!”

Mother had said I was supposed to stay with Yu-ri, but she’d also called for us to return to the boat. I made a spilt second decision, took a few deeps breaths, and followed Yu-ri. We went to the same shelf where we’d been harvesting sea urchins. Yu-ri dragged herself along the craggy surface, pulled out her bitchang, jabbed it in a hole, and pulled out an octopus. It was huge! The arms must have been a meter long. Such a catch! I would get some credit for it too.

The octopus reached out and looped an arm around my wrist. I yanked it loose. By the time I’d done that, some of its other limbs had grabbed onto Yu-ri. One had reached my thigh and was pulling me toward it, while another was slithering sucker over sucker up my other arm. I struggled to pull them off. The octopus’ bulbous head moved towards Yu-ri’s face, but she was so busy fighting the other arms that were pulling her closer into its grip that she didn’t notice. I wanted to scream for help, but I couldn’t. Not underwater.

Before another moment passed, Yu-ri’s face was covered. Instead of fighting or resisting, I swam closer, linked my arms around the octopus and Yu-ri, and kicked as hard as I could. As soon as we breached the surface, I yelled, “Help! Help! Help us!”

The octopus was strong. Yu-ri’s face was still covered. The creature was trying to pull us back under. I kicked and kicked. Suckers loosened from Yu-ri and came to me, sensing I was now the greater threat. They creeped along my arms and legs.

I heard splashing, then arms grabbed me. Knives flashed in the sun as suckers were pried from my skin, chunks of the octopus cut off, and tossed through the air, discarded. Buoyed by the others, I lifted a leg so they could remove the suckers. When I caught a glimpse of my mother’s face, fierce in concentration, I knew I’d be safe. Women worked on Yu-ri too, but she didn’t seem to be helping them. Do-saeng pulled her arm back, her knife in her fist. If I were her, I would have used all my strength to stab the octopus’ head, but she couldn’t. Yu-ri was underthere. Do-saeng went up under the octopus’s head, running the blade parallel to her daughter’s face. Even with all the women surrounding us, I could feel in my legs that I was the one keeping Yu-ri afloat even as the octopus continued to try to drag us under. The limpness of Yu-ri’s body in my arms told me something the others hadn’t yet realized. As strong as I wanted to be, I began to cry inside my goggles.

The women worked their way up to the thicker parts of the octopus’ appendages. That, combined with the repeated jabs and pokes to the octopus’ head from the tip of Do-saeng’s knife, thoroughly weakened the creature. It was either dead or close to it, but like a lizard or a frog, its body still had impulses and strength.

Finally, I was free.

“Can you swim to the boat?” Mother asked.

“What about Yu-ri?”

“We’ll take care of her. Can you make it alone?”

I nodded, but now that the battle was over, whatever had caused me to fight so hard was dissipating fast. I made it about halfway to the boat before I had to flip onto my back to float and rest for a moment. Above me, clouds traveled quickly, pushed by the wind. A bird flew overhead. I closed my eyes, trying to draw on deeper strength. Waves lapped against my ears—submerging them one moment, then exposing them to the worried sounds of the women still with Yu-ri. I heard a splash, then a second, and a third. Arms once again supported me. I opened my eyes: Mi-ja and the Kang sisters. Together they helped me to the boat. Gu-ja, the strongest of us, heaved herself up and over the side. I placed my arms on the side of the boat and began to pull myself up, but the ordeal had left me too weak. Mi-ja and Gu-sun each placed a hand under my bottom and pushed me up. I slipped to the deck like a caught fish. I lay there panting, my limbs like rubber, my mind exhausted. I pulled my goggles from my eyes, and they clattered to the deck. The whole while, the three girls babbled nonstop.

“Your mother said we should stay in the boat—”

“She didn’t want us to help—”

“Baby-divers would only cause more problems—”

“In a rescue—”

I could barely take in what they said.

Other women began to arrive. I forced myself to sit up. Mi-ja and the Kangs went to the edge of the boat and reached down their arms. I joined them and helped grab Yu-ri. She felt heavy—a dead weight. We pulled her up and over, and we fell back to the deck. Yu-ri lay on top of me, not moving. The boat pitched, and she rolled to the side. Do-saeng came next, followed by my mother. They knelt next to Yu-ri. As the other haenyeo clambered aboard, Mother lowered her cheek to Yu-ri’s mouth and nostrils to feel if any breath escaped.

“She’s alive,” Mother said, sitting back on her heels. Do-saeng and some of the other haenyeo began to rub Yu-ri’s limbs, trying to bring life back into them. Yu-ri didn’t respond. “We should try to empty her of water,” Mother suggested. Do-saeng edged out of the way. Mother pressed hard on Yu-ri’s chest, but nothing came out of her mouth. Unsuccessful, Mother said, “We must consider that the octopus saved her life by covering her face. Otherwise she would have inhaled water…”

The other women circled back in for their massaging.

Mother suddenly turned her attention to Mi-ja, the Kang sisters, and me. She regarded us, considering our actions. We were supposed to stay together. Mi-ja and the Kangs had, but they lookedembarrassed. Mother didn’t have to say a word before the excuses began to sputter out.

“I saw her the last time I came up for air,” Gu-sun stammered.

“We were never out of Yu-ri’s sight,” Mi-ja choked out. “She watched over us all day.”

“She said she saw something big,” I mumbled.

“And the two of you went. I saw you go, even though I’d sounded the call.”

I couldn’t bear that Mother would think I’d been partly responsible for what had happened to Yu-ri, so I said, “We didn’t hear you.” I lowered my gaze and shivered—from shock, sadness, and now shame that I’d lied to my mother.

Mother shouted for everyone to take their places. We picked up our oars. The boat lurched as it began moving over and through the white-capped waves. Do-saeng remained by her daughter’s side, pleading with her to wake up. Yu-ri’s future mother-in-law took responsibility for leading our song. “My shoulders on this icy night shake along with the waves. This small woman’s mind shivers with the grief of a lifetime.” It was so mournful that soon we all had tears running down our cheeks.

Mother placed a blanket over Yu-ri and another over Do-saeng’s shoulders. Do-saeng wiped her face with a corner of the rough cloth. She spoke, but her words were carried away by the wind. First one woman then another stopped singing, each of us needing to hear Do-saeng. Yu-ri’s future mother-in-law kept our rowing rhythm going by beating the wooden handle of a diving tool on the edge of the boat.

“A greedy diver equals a dead diver,” Do-saeng lamented. We all knew the saying, but to hear it from a mother about her own daughter? That’s when I learned just how strong a mother must be. “This is a haenyeo’s worst sin,” she went on. “I want that octopus. I can sell it for a lot of money.”

“Many things exist under the sea that are stronger than we are,” Mother said.

She wrapped an arm around Do-saeng, who then expressed her worst fear. “What if she doesn’t wake up?”

“We have to hope she will.”

“But what if she remains like this—suspended between this world and the Afterworld?” Do-saeng asked, gently lifting her daughter’s head and placing it in her lap. “If she’s unable to dive or work in the fields, wouldn’t it be better to let her go?”

Mother pulled Do-saeng in closer. “You don’t mean that.”

“But—” Do-saeng didn’t finish her thought. Instead, she smoothed strings of wet hair away from her daughter’s face.

“None of us yet know what the goddesses have planned for Yu-ri,” Mother said. “She may wake up tomorrow her usual chatterbox self.”

# # #

Yu-ri didn’t wake up the next morning. Or the morning after that. Or the week after that. In desperation, Do-saeng sought help from Shaman Kim, our spiritual leader and guide, our divine wise one. Although the Japanese had outlawed Shamanism, she continued to perform funerals and rites for lost souls in secret. She was known to hold rituals for grandmothers when their eyesight began to fade, mothers whose sons were in the military, and women who had bad luck, such as three pigs dying in a row. She was our conduit between the human world and the spirit world. She had the ability to go into trances to speak to the dead or missing, and then transmit their messages to friends, family, and even enemies. Do-saeng hoped Shaman Kim would now reach Yu-ri’s soul and bring her mind back to her body and her family.

The ritual was held in Do-saeng’s home. Shaman Kim and her helpers wore colorful hanboks—traditional Korean gowns from the mainland—instead of Jeju’s usual drab trousers and jackets. Her assistants banged on drums and cymbals. Shaman Kim spun, her arms raised, calling out to the spirits to return the young haenyeo to her mother. Do-saeng openly wept. Jun-bu, Yu-ri’s brother, who was just beginning to develop peach fuzz on his cheeks, tried to hold in his emotions, but we all knew how much he loved his sister. Yu-ri’s future husband was pale with grief, and his parents did their best to comfort him. It was painful to see their sorrow. Still Yu-ri didn’t open her eyes.

That night, I told Mi-ja my secret—that Yu-ri had asked me to disobey my mother, and I had. “If I hadn’t agreed to go down one more time, Yu-ri wouldn’t be the way she is now.”

Mi-ja tried to comfort me. “It was Yu-ri’s duty to watch over you. Not the other way around.”

“I still feel responsible, though,” I admitted.

Mi-ja mulled that over for a few moments. Then she said, “We’ll never know why Yu-ri did what she did, but don’t tell anyone your secret. Think of the pain it will bring to her family.”

I also thought of the agony it would bring Mother. Mi-ja was right. I had to keep this a secret.

# # #

After another week, Do-saeng asked Shaman Kim to try again. This time the ceremony was held in our bulteok—hidden from the prying eyes of the Japanese. In fact, no men attended. Not even Yu-ri’s brother. Do-saeng carried her daughter to the bulteok and lay her next to the firepit. An altar had been set up against the curved stone wall. Offerings of food—so scarce—sat in dishes: a pyramid of oranges, bowls holding the five grains of Jeju, and a few jars of homemade alcohol. Candles flickered. Mother had offered to pay Jun-bu to write messages for Yu-ri on long paper ribbons. He did it for free. “For my sister,” he told me when I went to his family’s house to pick them up. Now the ends of the ribbons had been tucked into the wall’s rocky crevices, their tails flapping in the breeze that squeezed through the cracks.

Shaman Kim wore her most colorful silk hanbok. A sash the tint of maple leaves in spring tied closed the bright blue bodice. The main part of the fuchsia gown was so light that it wafted about her as she moved through the ceremony. Her headband was red, and her sleeves gleamed the hue of rapeseed flowers.

“Given the dominance on Jeju of volcanic cones, which are concave at the top like a woman’s private parts, it is only natural that on our island females call and males follow,” she began. “The goddess is always supreme, while the god is merely a consort or guardian. Above all these is the creator, the giant Goddess Seolmundae.”

“Grandmother Seolmundae watches over us all,” we chanted together.

“As a goddess, she flew over the seas, looking for a new home. She carried dirt in the folds of her skirt. She found this spot where the Yellow Sea meets the East China Sea and began to build herself a home. Finding it too flat, she used more of the dirt in her gown, building the mountain until it was high enough to reach the Milky Way. Soon her skirt became worn and tiny holes formed in the cloth. Soil leaked from it, building small hills, which is why we have so many oreum. In each one of these volcanic cones, another female deity lives. They are our sisters in spirit, and you can always go to them for help.”

“Grandmother Seolmundae watches over us all,” we chanted.

“She tested herself in many ways, as all women must,” Shaman Kim told us. “She assessed the waters to see how deep they were, so that haenyeo would be safe when they went to sea. She also searched ponds and lakes, looking for ways to improve the lives of those who worked the fields on land. One day, attracted to a mysterious mist on Muljang-ol Oreum, she discovered a lake in its crater. The water was deep blue, and she could not begin to guess its depths. Taking one big breath, she swam straight down. She has never returned.”

Several of the women nodded appreciatively at the good telling of this story.

“That’s one version,” the shaman continued. “Another says Grandmother Seolmundae, like all women, was exhausted by all she did for others, especially for her children. Her five hundred sons were always hungry. She was making them a cauldron of porridge when she became drowsy and fell into the pot. Her sons looked everywhere for her. The youngest son finally found all that remained of her—just bones—at the bottom of the pot. She had died from mother love. The sons were so overcome that they were instantly petrified into five hundred stone outcroppings, which you can see even today.”

Do-saeng silently wept. The story helped one suffering mother to hear of another suffering mother.

“The Japanese say ifGrandmother Seolmundae existed and ifthat oreum was the water pathway to her underwater palace,” Shaman Kim went on, “then she abandoned us, as have all our goddesses and gods. I say she never left us.”

“We sleep on her every night,” we recited. “We wake on her every morning.”

“When you go into the sea, you dive among the underwater ripples of her skirt. She is the great volcano at the center of our island. Some people call it Mount Halla, the Peak That Pulls Down the Milky Way, or the Mountain of the Blessed Isle. To us, she isour island. Anywhere we go, we can call to her and weep out our woes, and she will listen.”

Shaman Kim now directed her attention to Yu-ri, who had not once stirred.

“We are here to help Yu-ri with her traveling-soul problem, but we must also worry about those of you who’ve suffered soul-loss, which happens any time a person receives a shock,” she said. “Your collective has experienced a terrible blow. None has suffered more than Yu-ri’s mother. Do-saeng, please kneel before the altar. Anyone else who is in anguish, please join her.”

My mother knelt next to Do-saeng. Soon the rest of us were on our knees in a circle of anguish. The shaman held ritual knives in her hands from which white ribbons streamed. As she sliced through negativity, the ribbons swirled around us like swallows through the air. Her hanbok ballooned in clouds of riotous color. We chanted. We wept. Our emotions flowed from us accompanied by the cacophony of cymbals, bells, and drums played by Shaman Kim’s assistants.

“I call upon all goddesses to bring Yu-ri’s spirit back from the sea or wherever it is hiding,” Shaman Kim implored. After making this request another two times, her voice changed as Yu-ri inhabited her. “I miss my mother. I miss my father and my brother. My future husband. . . Aigo. . .” The shaman turned to my mother. “Diving chief, you sent me here. Now bring me home.”

The way Yu-ri’s voice came out of Shaman Kim’s mouth sounded more like blame than an entreaty for help. This was not a good portent. Shaman Kim seemed to acknowledge this. “Tell me, Sun-sil, how would you like to respond?”

My mother rose. Her face looked taut as she addressed Yu-ri. “I accept responsibility that I sent you into the sea, but I gave you a single duty that day: to stay with my daughter and help the Kang sisters as they looked after Mi-ja. You were the eldest of the baby-divers. You had an obligation to them and to us. Through your actions, I could have lost my daughter.”

Perhaps only I could see how deeply affected Mother was by what had happened. I was both awed and humbled. I hoped one day I could prove to her that I loved her as much as she loved me.

Shaman Kim swiveled to Do-saeng. “What do you wish to tell your daughter?”

Do-saeng spoke sharply to Yu-ri. “You would blame another for the results of your greed? You embarrass me! Leave greed where you are and come home right now! Don’t ask someone else to help you!” Then she softened her tone. “Dear girl, come back. Your mother and brother miss you. Return home and we will drench you in love.”

Shaman Kim chanted a few more incantations. The helpers banged their cymbals and drums. After that, there was nothing left to say or do.

The next morning, Yu-ri woke up. She was not the same girl, though. She could smile, but she could not speak. She could move, but she limped and sometimes jerked her arms. Both sets of parents agreed that a marriage was no longer possible. Mi-ja and I hung onto my secret, which made us closer than ever. In the weeks that followed, after we’d worked in the dry or wet fields, we visited Yu-ri. Mi-ja and I talked and giggled, so Yu-ri would have the sense she was still a young girl with no worries. Sometimes Jun-bu joined us and read aloud the essays he was writing for school or tried to tease us as he had once teased his sister. On other days, Mi-ja and I helped Do-saeng wash Yu-ri’s body and hair. And when the weather grew warm, Mi-ja and I took her to the shore, where we sat in the shallows to let the smallest wavelets lap against her. We told stories, we patted her face, we let her know we were there, and she would reward us with a beautiful smile.

Every time I visited, Do-saeng bowed and expressed her gratitude. “If not for you, my daughter would have died,” she’d say as she poured buckwheat tea or presented me with a dish of salted smelt, but her eyes sent a darker message. She may not have known exactly what part I’d played in Yu-ri’s accident, but she certainly suspected that it was more than I’d let on, either to her or my mother.

Discussion Guide

The Island of Sea Women by Lisa See

This reading group guide for The Island of Sea Women includes discussion questions and ideas for enhancing your book club. We hope that this guide will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

- The story begins with Young-sook as an old woman, gathering algae on the beach. What secrets or clues about the past and the present are revealed in the scenes that take place in 2008?Why do we only understand the beginning of the novel after we have finished it?

- When Young-sook and Mi-ja are fifteen, Young-sook’s mother says to them: “You are like sisters, and I expect you to take care of each other today and every day as those tied by blood would do.” (Page 13) How are these words of warning? The friendship between Young-sook and Mi-ja is just one of many examples of powerful female relationships in the novel. Discuss the ways in which female relationships are depicted and the important role they play on Jeju.

- On page 17, Young-sook’s mother recites a traditional haenyeo aphorism: Every woman who enters the sea carries a coffin on her back.But she also says that the sea is like a mother. (Page 22.) Then, on page 71, Grandmother says, “The ocean is better than your natal mother. The sea is forever.” How do these contradictory ideas play out in the novel? What do they say about the dangerous work of the haenyeo?

- In many ways, the novel is about blame, guilt, and forgiveness. In the first full chapter, Yu-ri has her encounter with the octopus. What effect does this incident have on various characters moving forward: Mother, Young-sook, Mi-ja, Do-seang, Gu-ja, Gu-sun, and Jun-bu? Young-sook is also involved in the tragic death of her mother. To what extent is she responsible for these sad events? Is her sense of guilt justified?

- Later, on page 314, Clara recites a proverb attributed Buddha: To understand everything is to forgive. Considering the novel as a whole, do you think this is true? Young-sook’s mother must forgive herself for Yu-ri’s accident, Young-sook must forgive herself for her mother’s death, Gu-sun forgives Gu-ja for Wan-soon’s death.On a societal level, the people of Jeju also needed to find ways to forgive each other. While not everyone on Jeju has found forgiveness, how and why do you think those communities, neighbors, and families have been able to forgive? Do you think anything can be forgiven eventually? Should it? Does Young-sook take too long to forgive given what she witnessed?

- Mi-ja carries the burden of being the daughter of a Japanese collaborator. Is there an inevitability to her destiny just as there’s an inevitability to Young-sook’s destiny? Another way of considering this aspect of the story is, are we responsible for the sins of our fathers (or mothers)? Later in the novel, Young-sook will reflect on all the times Mi-ja showed she was the daughter of a collaborator. She also blames Yo-chan for being Mi-ja’s son, as well as the grandson of a Japanese collaborator. Was Young-sook being fair, or had her eyes and heart been too clouded?

- The haenyeo are respected for having a matrifocial culture—a society focused on women. They work hard, have many responsibilities and freedoms, and earn money for their households, but how much independence and power within their families and their cultures do they really have? Are there other examples from the story that illustrate the independence of women but also their subservience?

- What is life like for men married to haenyeo? Compare Young-sook’s father, Mi-ja’s husband, and Young-sook’s husband.

- On page 189, there is mention of haenyo from a different village rowing by Young-sook’s collective to share gossip. How fast did information travel around the island and from the mainland? Was the Five-Day Market a good source of gossip or were other places were more ideal? On page 201, Jun-bu mentions his concern about believing information broadcast on the radio, “… but can we trust anything we hear?” Were there specific instances when information broadcast on the radio was misleading or false? What impacts how people hear and interpret the news?

- Confucianism has traditionally played a lesser role on Jeju than elsewhere in Korea, while Shamanism is quite strong. What practical applications does Shamanism have for the haenyeo? Do the traditions and rituals help the haenyeo conquer the fear and anxieties they have about the dangerous work they do? Does it bring comfort during illness, death, and other tragedies? Does Young-sook ever question her beliefs, and why?

- On page 39, Young-sook’s mother recites the aphorism If you plant red beans, then you will harvest red beans. Jun-bu repeats the phrase on page 199. How do these two characters interpret the saying? How does this saying play out for various characters?

- At first it would seem that the visit of the scientists to the island is something of a digression. What important consequences does the visit have for Young-sook and the other haenyeo?

- The aphorism “Deep roots remain tangled underground,” is used to describe Young-sook’s and Mi-ja’s friendship, and it becomes especially true when it’s revealed that their children, Joon-lee and Yo-chan, are getting married. How else does this aphorism manifest itself on Jeju, especially in the context of the islanders’ suffering and shared trauma? Do you think it’s true that we cannot remove ourselves from the connections of our pasts?

- On page 120, Young-sook’s mother-in-law, Do-Saeng, says “There’s modern, and then there’s tradition.” How does daily life on Jeju change between 1938 and 2008?Discuss architecture, the arrival of the scientists and the studies they conduct, the introduction of wet suits and television, etc. How does Young-sook reconcile her traditional haenyeoway of life with the encroaching modern world? Do you think it’s possible to modernize without sacrificing important traditional values?

- The characters have lived through Japanese colonialism, the Sino-Japanese War, World War II, the Korea War, the 4.3 Incident, and the Vietnam War. How do these larger historic events impact the characters and island life?

- Mi-ja’s rubbings are critical to the novel. How do they illustrate the friendship between Mi-ja and Young-sook? How do they help Young-sook in her process of healing?

Enhance Your Book Club and Deepen Your Discussion

- Consider reading Lisa See’s Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, which follows a lifelong friendship between two women in 19th century China. Compare this friendship to the friendship between Young-sook and Mi-ja.

- To learn how to have your own Korean Tea & Tasting Package for Book Clubs, click here.

- Time yourselves to see how long you can hold your breath. Now think about holding your breath for two minutes.

- In The Island of Sea Women, there’s an expectation that a daughter should follow in her mother’s footsteps. Did this surprise you? Discuss how common you think it is even today for daughters to follow in their mothers’ footsteps—personally or professionally.

- If you have access to one, visit your local Korean history or art museum.

- Visit Step Inside the World of The Island of Sea Women to see maps, photos, and videos, and to learn about the haenyeo and Lisa’s research.

Videos

Lessons from Jeju | Freediving and Motherhood with Kimi Werner

Documentary: 12 year old Korean Haenyeo Diver in 1975

This film documents a day in the life of a 12 year old Korean girl, learning to dive as a haenyeo on the island of Jeju. This novice diver is of the last generation that will engage in this vocation, and serves as an important historical document.

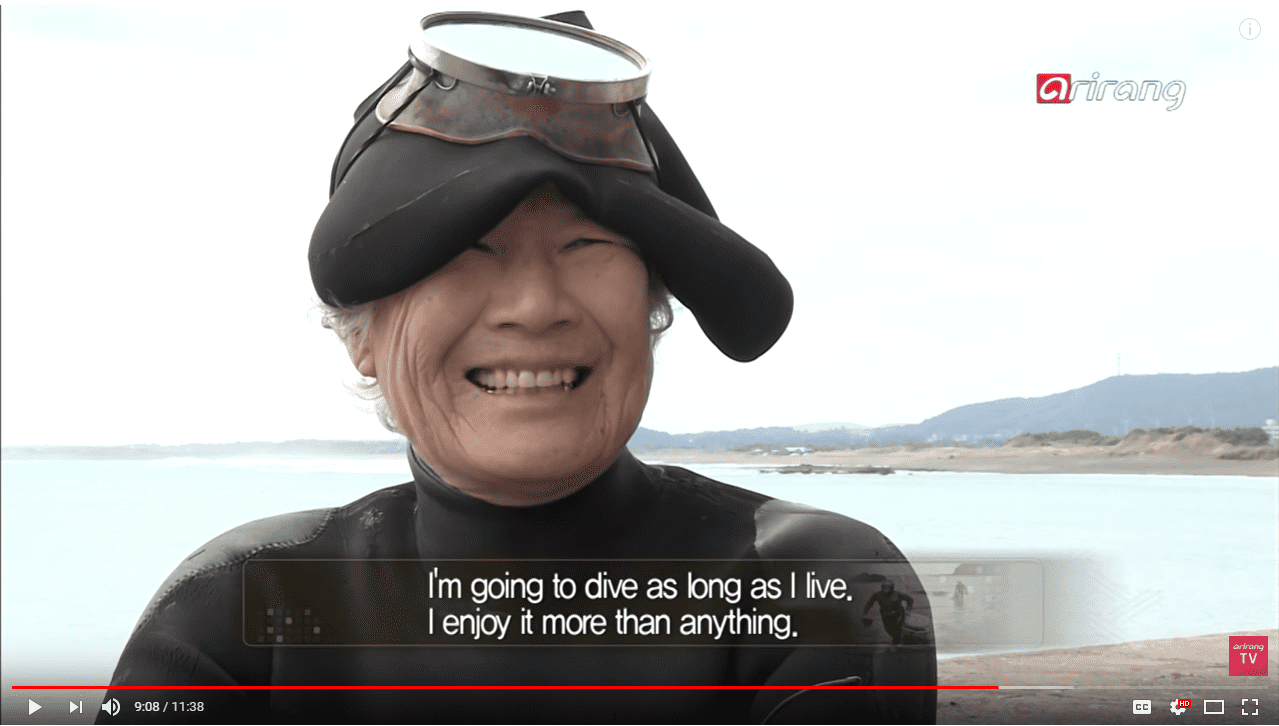

100 Icons of Korean Culture: The Haenyeo of Jeju (Episode 15)

Diving with the last generation of Korea’s Mermaids by Heidi Shin

I’m on a boat with a group of Korean grandmothers—but it’s not a cruise ship and there’s no shuffleboard in sight. It’s a motorboat and these elderly ladies are sporting wetsuits and goggles. They’re in their 60s, 70s, even 80s, and they’re about to jump into the ocean with what look like small garden hoes in hand. READ MORE

Sea Women Documentaries

The Women Divers of Jeju Island – Talk by Brenda Paik Sunoo

Frequently Asked Questions

(FAQ)

I was sitting in my doctor’s waiting room, leafing through magazines, as we all do. I came across a tiny article—just one paragraph and one small photo—about the diving women of Jeju Island. I ripped it out of the magazine—yes, I’m one of those people—and took it home. I hung onto the article for eight years before I decided that now was the time to write about the haenyeo.

So many things! They have a matrifocal society. Not a matriarchy, but a society focused on women. The women hold their breath for two minutes and dive down sixty feet (deep enough to get the bends) to harvest seafood. They are the breadwinners in their families, while their husbands take care of the children and do the cooking. In the past, women would retire at age fifty-five. Today, the youngest haenyeo is fifty-five. When I was on Jeju, I interviewed women in their seventies, eighties, and nineties—many of whom are still diving. It’s said that within a few years, this culture will be gone from the world. That’s one of the reasons that they’ve received designation from UNESCO as an Intangible World Heritage Tradition. I felt compelled to write about them while I still could.

We need to remember that women writers haven’t been getting published for all that long. Yes, there are the few women that we all know about—the Bronte sisters, Emily Dickinson, George Sand, Virginia Woolf, and a few others—but really they were few and far between. This means that in literature most female relationships—mothers and daughters, sisters, friends—have been written by men. I find it extremely exciting to read about female relationships through the eyes of women and, again, this is still a relatively recent phenomenon. And there’s such range to that, right? Chick-lit women who shop, tough women detectives, flawed women, brave women, poor women, rich women, women from other cultures, religions, cultures, and traditions. As a writer, I’m drawn to women’s friendship because it’s unlike any other relationship we have in our lives. We will tell a friend something we won’t tell our mothers, our husbands, boyfriends, lovers, or our children. This is a particular kind of intimacy, and it can leave us open to the deepest betrayals.

I had some truly great experiences interviewing women in their homes, but my favorite interviews were with the women who sit on the beach to gather and sort the algae and seaweed that’s washed ashore overnight. They’re retired, semi-retired, or getting over an injury. They’re loud, because their ears have been damaged by years of diving. They’re very direct. If a woman doesn’t want to talk, she’ll shout, “Go away!” They told me wonderful, funny, and sometimes very sad stories. They’re very aware of everything going on around them. This also comes from their years in the sea and having to be aware of all potential dangers.

On a purely person level, I wanted to set part of the novel in the present, because I’d so enjoyed talking to the women on the beach and wanted to relive it in my writing. Far more important, the novel is about forgiveness. What happens when you don’t forgive, what does it take to forgive, what are the consequences for individual people, communities, and countries (or in this case an island) when you do or don’t forgive? I wanted to start with the consequences, which meant having scenes set in the present. They allowed me to reveal hints about the past but also lay the groundwork for what would happen in the next section.

A challenge? But there were so many! Some were tiny and really have to do with logistical things like how to get someone from a small village to Jeju’s main port in the 1930s or how exactly did a diver get from Jeju to Russia in the 1930s and 1940s. Others are huge. For example, looking deeply at forgiveness was a personal challenge for me. But I’d have to say that the scenes which were the absolute hardest had to do with the 4.3 Incident. This book has the most violent scene of any I’ve ever written, and I hope never to write another one like it again. That scene is based on what actually happened in Bukchon, and I felt I had to honor the people who died by writing as truthfully as I could. Beyond that, that scene sets up the whole question of forgiveness. When the worst thing happens, can you ever forgive? I felt readers had to have a visceral understanding of what was lost that day. I wanted readers to think, What if that happened to me? That meant I had to go there, and it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my writing.

Step Inside: